[#78] Banking in India: FDI investment, bank consolidation, and the "great re-bundling"

PSU and RRB consolidation, Japanese investment in Indian BFSI, all banks becoming universal banks, and fintechs becoming SFBs with a path to full banks signify changes in India's banking sector

Hi folks - and welcome to the first Painted Stork newsletter of 2026 🚀

Hope everyone had a restful New Year. To kick things off, I wanted to start with something fundamental: how the banking ecosystem in India is evolving. Banks sit at the core of fintech, money movement, and credit creation, and a lot of the shifts we’re seeing across fintech right now make much more sense when you look at what’s happening here.

So for the first edition of the year, this is a deep dive into how India’s banking stack is changing, and why that matters for the future of fintech.

A few interesting movements in India’s banking ecosystem signal where the industry is headed in the next 3-5 years:

AU Small Finance Bank → universal bank license (2025)

Fino Payments Bank → Small Finance Bank license (2025)

Protean (an AA) → 4.95% stake in NSDL Payments Bank (2025)

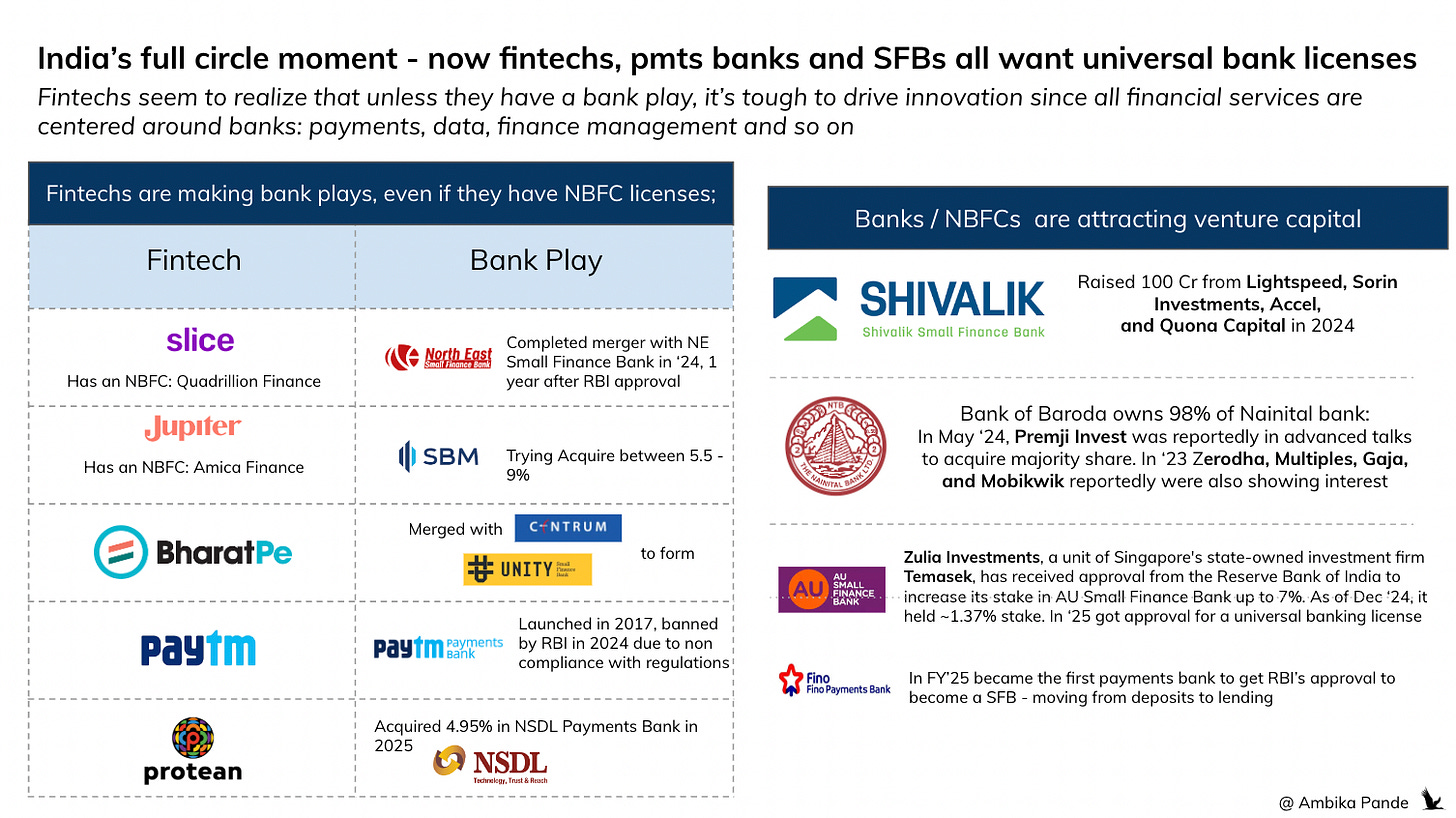

This tracks with a broader trend: fintechs going after banks through mergers and acquisitions. Slice merged with North East Small Finance Bank to form Slice SFB (Dec ‘24). BharatPe and Centrum formed Unity SFB. Paytm was a payments bank until it got banned, I expect it to revive once it pays its regulatory dues.

There are emerging themes that seem to be driving the evolution of the banking sector

1️⃣ Government / policy themes

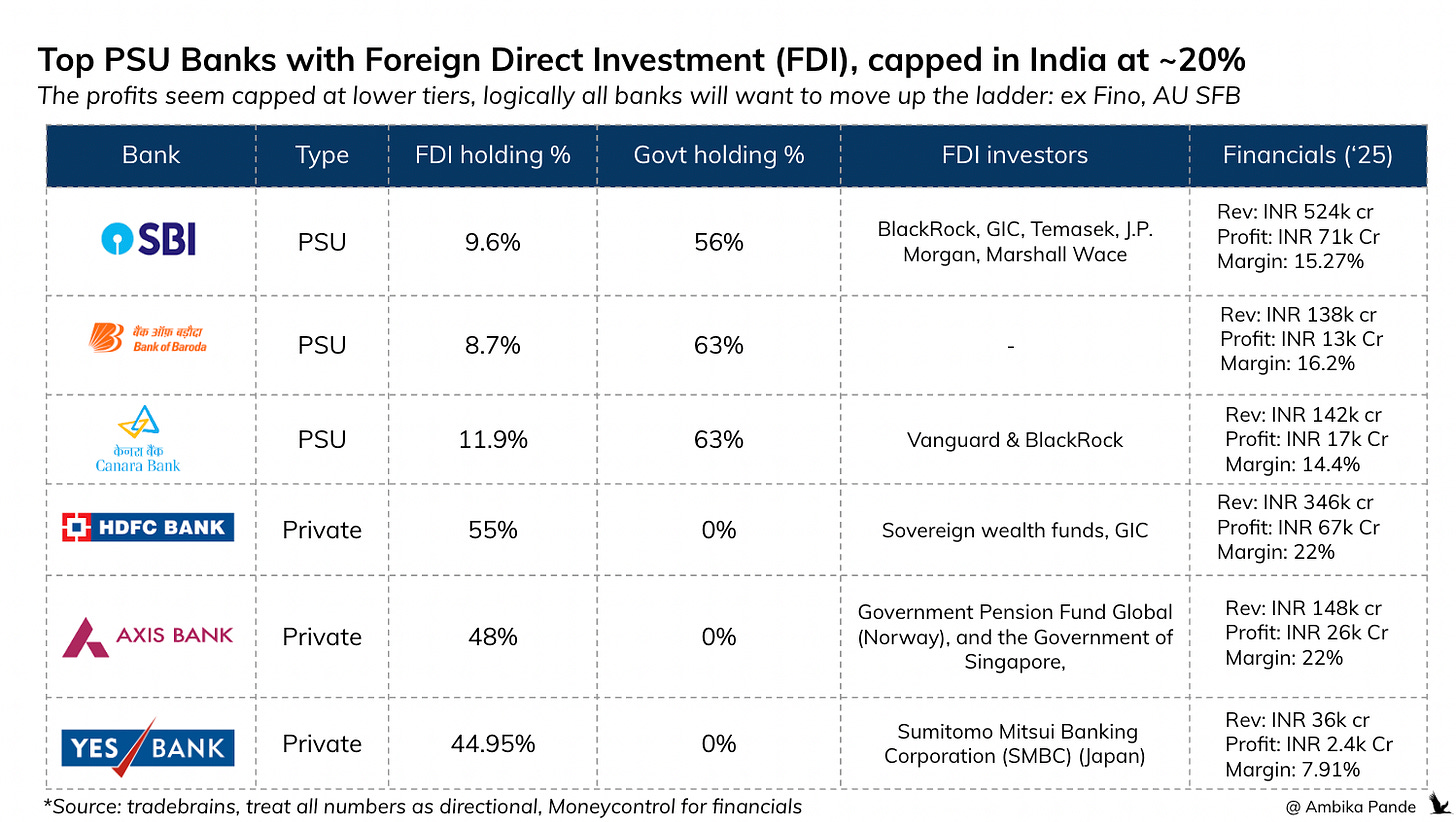

RBI wants to drive FDI in PSU banks to increase governance, transparency and capital efficiency. The current cap is ~20%. While it’s unlikely this will jump to ~49% (as recent news suggests), most PSUs currently have ~10% FDI, so we could see an influx of foreign capital.

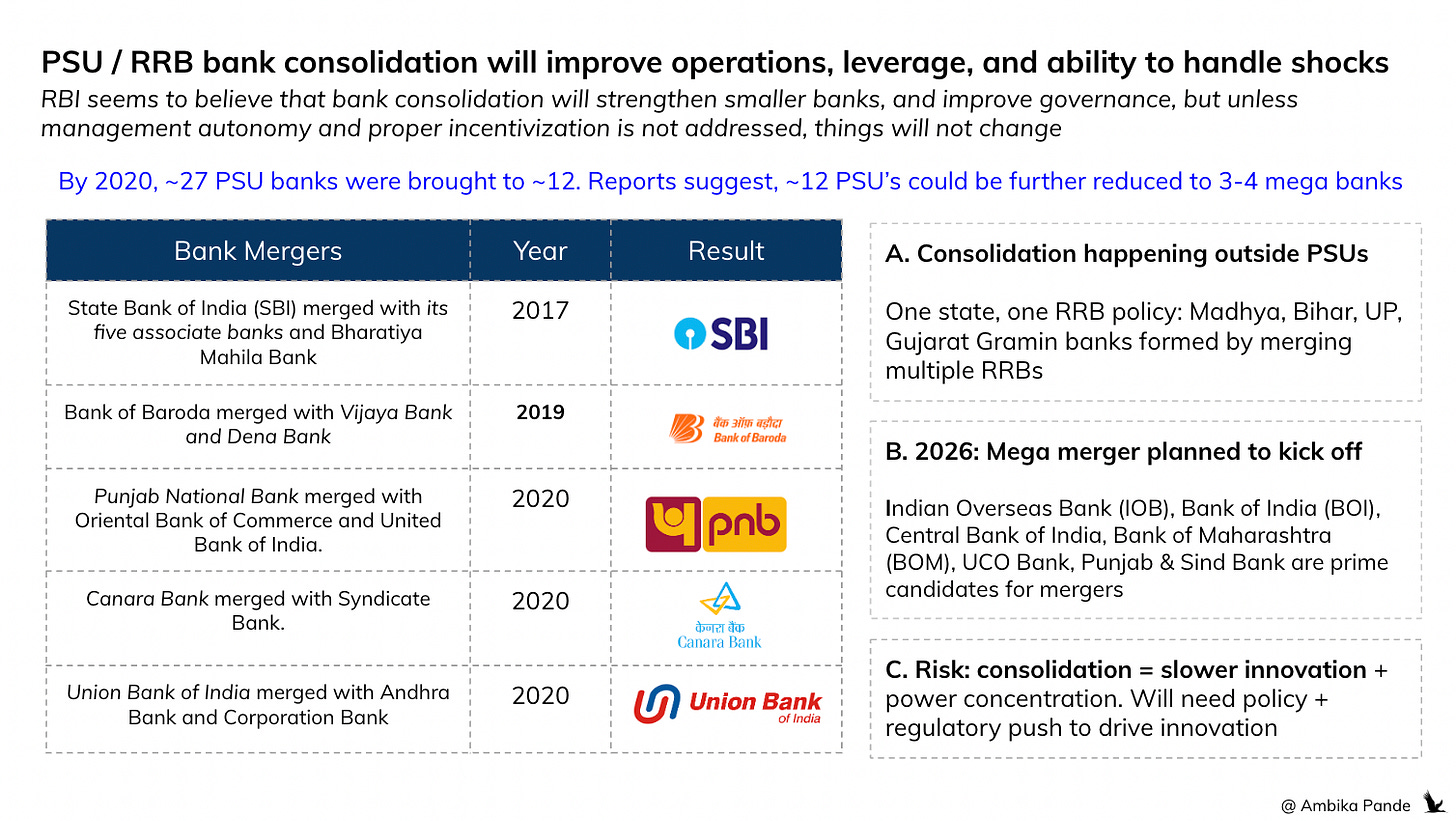

RBI wants to consolidate smaller PSU and RRB banks to improve scale, strength, and governance. Phase one completed ~2020: PSUs reduced from 27 to 12. Major mergers included SBI with its 5 associate banks and Bharatiya Mahila Bank; Bank of Baroda with Vijaya and Dena Bank; and similar consolidations at Canara, PNB, and Union Bank.

2️⃣ Long term monetization strategy needs

I’ve written extensively about how fintechs in India are moving to full stack or lending due to limited monetization avenues. TLDR on how this is playing out with banks:

Fintechs becoming banks: There’s a clear pattern of fintechs wanting bank licenses to control more outcomes. Slice formed Slice SFB. Jupiter has been pursuing a stake in SBM for 3 years. Paytm got a payments bank license before being banned. PayPal applied for a US bank charter in 2025.

Every bank wanting to become a Universal Bank: AU SFB pursuing universal bank status, Fino Payments Bank upgrading to SFB, and Protean buying into NSDL Payments Bank: all point to the same monetization imperative driving the industry.

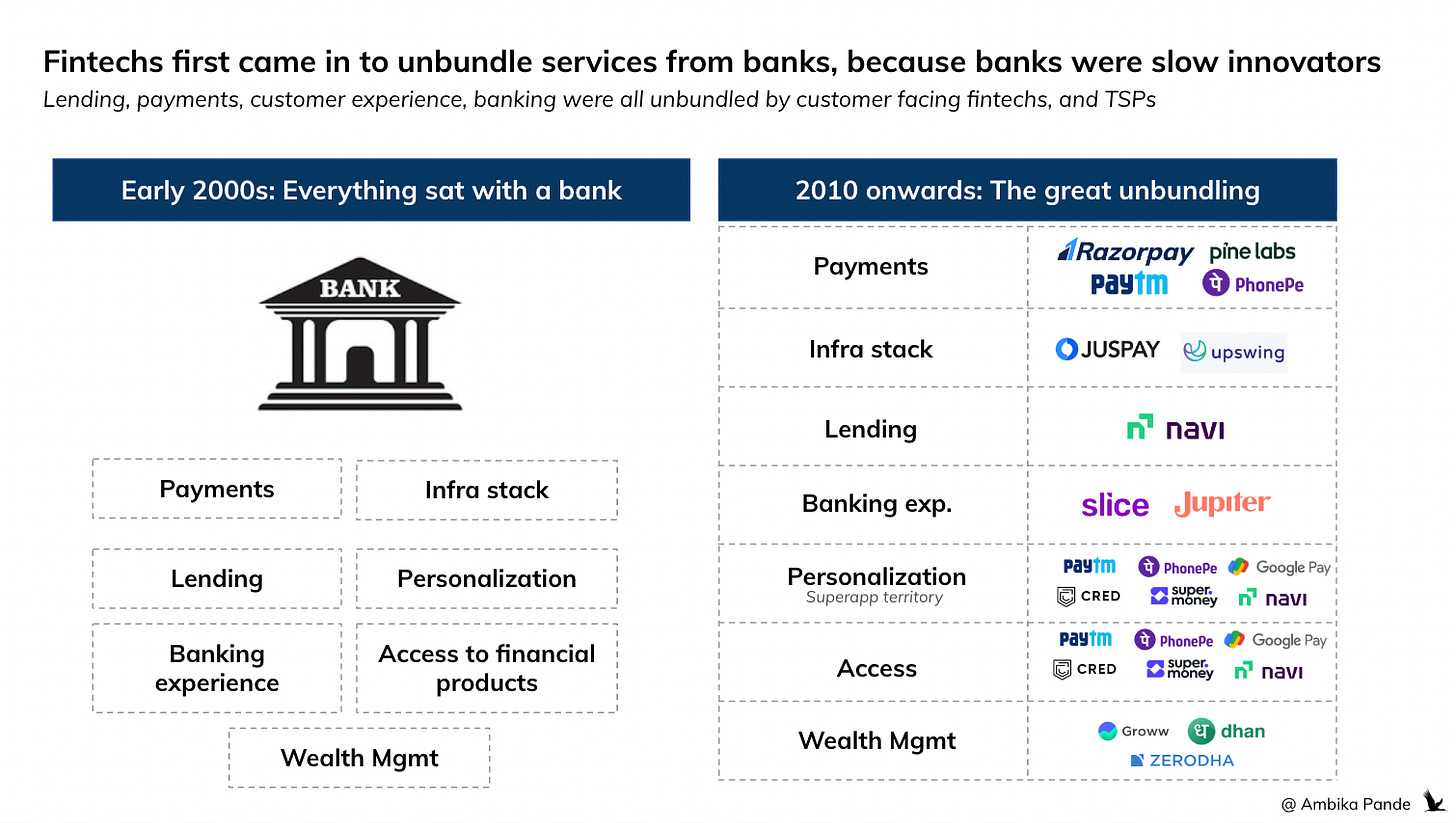

But why is everyone trying to become a bank? Fintechs first came into the picture because banks didn’t provide the optimal customer experience

Fintechs entered the market with a clear value proposition: banks weren’t providing optimal customer experience. “We’ll be the middlemen, optimize everything, and get your work done.” The market scaled, fintechs raised capital, and did a solid job redefining what financial offerings should look like:

Payment aggregation: Razorpay, Pine Labs, Cashfree

Neobanks and lending: Jupiter, Slice

Lending / BNPL: Zestmoney, Axio, Fibe

Payments and product access: PhonePe, Paytm, GPay, CRED

Wealth management: Zerodha, Groww, and vertical products like Stablemoney (FD-first)

Most of these companies were founded during India’s fintech boom: between 2015 and 2021 (Pine Labs, founded in 1998, is the obvious exception). The household names are customer- and merchant-facing platforms: the apps people use daily.

And there’s another layer, of further unbundling: fintechs working behind the scenes, enabling service delivery. The infrastructure players. Mindgate and Olive deploy UPI switches in bank infrastructure. Vegapay partnered with BharatPe and Paytm to launch Credit Lines on UPI. Falcon builds core management systems for banks. Finbox and Setu power lending journeys and bill payments: Setu runs CRED’s bill payment backend; Finbox raised $40M Series B from Westbridge.

The point being: fintechs started by unbundling the banking stack.

Fintechs showed up and said: let us own the customer. We’ll handle onboarding, support queries, and aggregate the banks. You focus on being a bank. Then TSPs. the fintech infrastructure players entered with a narrower pitch: there are specific technical flows (payments, lending, KYC) that need expertise. Let us own those. And all was well for a while.

Then, 2 things happened.

1. With billions pumped into fintech, companies adopted a “win at all costs” strategy.

Capital was abundant. This funded “grow at all costs, monetize later” strategies. A loss leader approach: acquire customers first, figure out revenue later. It made sense a decade ago. Then fintechs realized this doesn’t work. The expectation of zero-cost pricing became permanent. Even after gaining critical mass, raising prices meant newly-funded competitors would undercut them with near-zero pricing.

But the “zero pricing now, raise pricing later” strategy worked initially because pre-UPI, payment methods (cards, netbanking) had minimum pricing set by banks or networks: 2% MDR on cards, for example. Even if offered at a loss, merchants understood there was a cost, and that providers were subsidizing to let them trial the service. Pricing would eventually come.

The second part of the long-term monetization view was cross-sell. But unless you pulled off what Paytm did: Soundbox + lending innovation, it doesn’t work. Your core offering has to make money.

2. DPI: with UPI as the game changer came in mandated as free.

UPI now accounts for ~60% of payment volumes for any payment company. More if your average order value is around or below ₹1,500 (UPI’s AoV). With UPI expected to hit ~90% of total volumes, pricing pressure will only intensify.

This wasn’t just “a special merchant offer”: it created a market expectation that UPI is “supposed to be free.” Merchants refused to pay. Fair enough. (Credit on UPI, cards and credit lines may provide some rail monetization hope, but we’re still far from that.)

The result: UPI grew adoption, GMV, and MTU TAM, but compressed revenue TAMnot just for merchant-facing providers, but for everyone in the chain. Players building around DPI rails (payments, data sharing, identity, and now lending and e-commerce via OCEN, ONDC) had lower revenues.

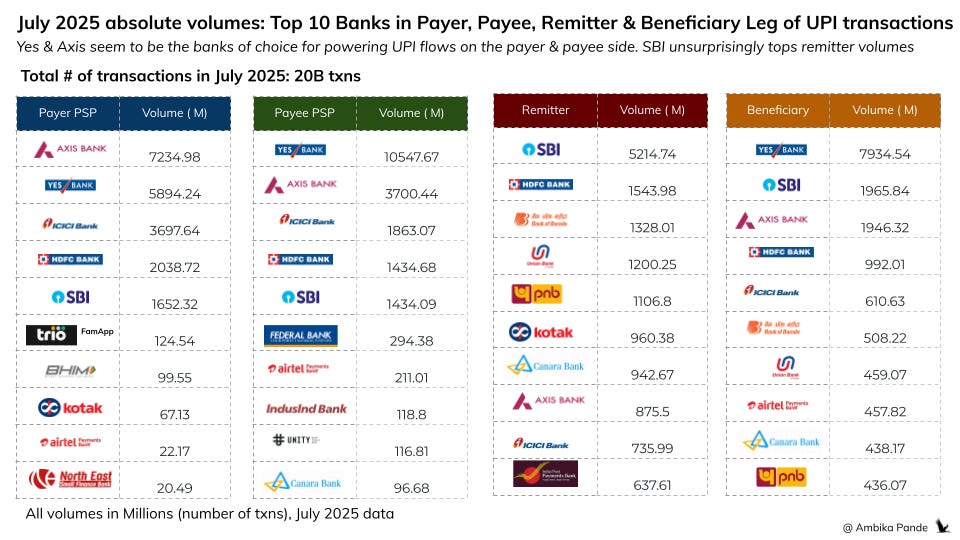

Eventually, banks, where core flows happen (UPI, AA) put their hands up: “Things may be free, but we have infra costs. You pay.” This is what happened with ICICI in July 2025 (and likely Yes Bank, Axis Bank the banks powering most UPI transactions).

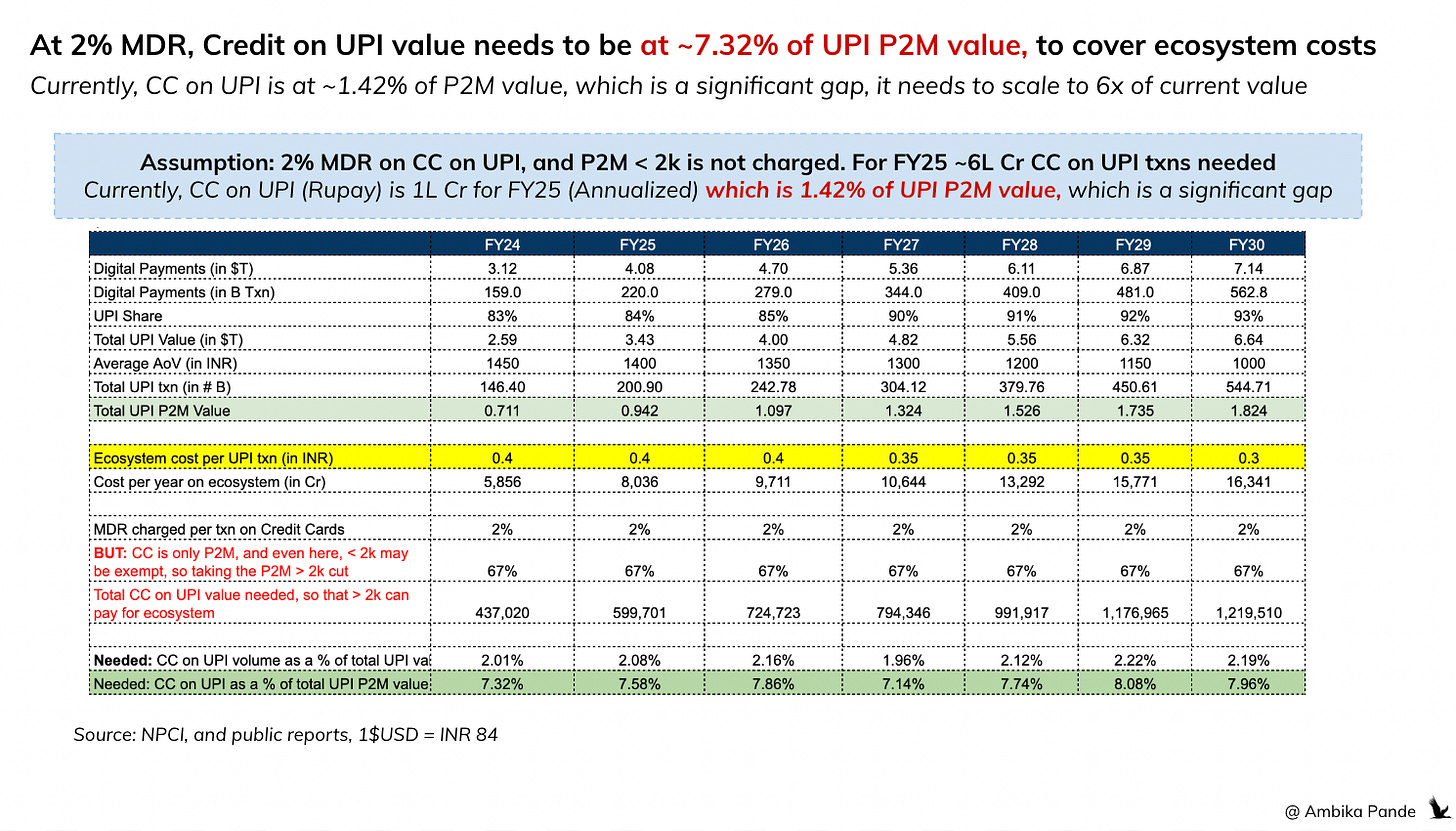

👇 I ran numbers on how much Credit on UPI (cards and lines) needs to scale to pay for the free UPI (on savings accounts) mandate. The numbers:

At 2% MDR, Credit on UPI needs to be at 7.32% of UPI P2M value

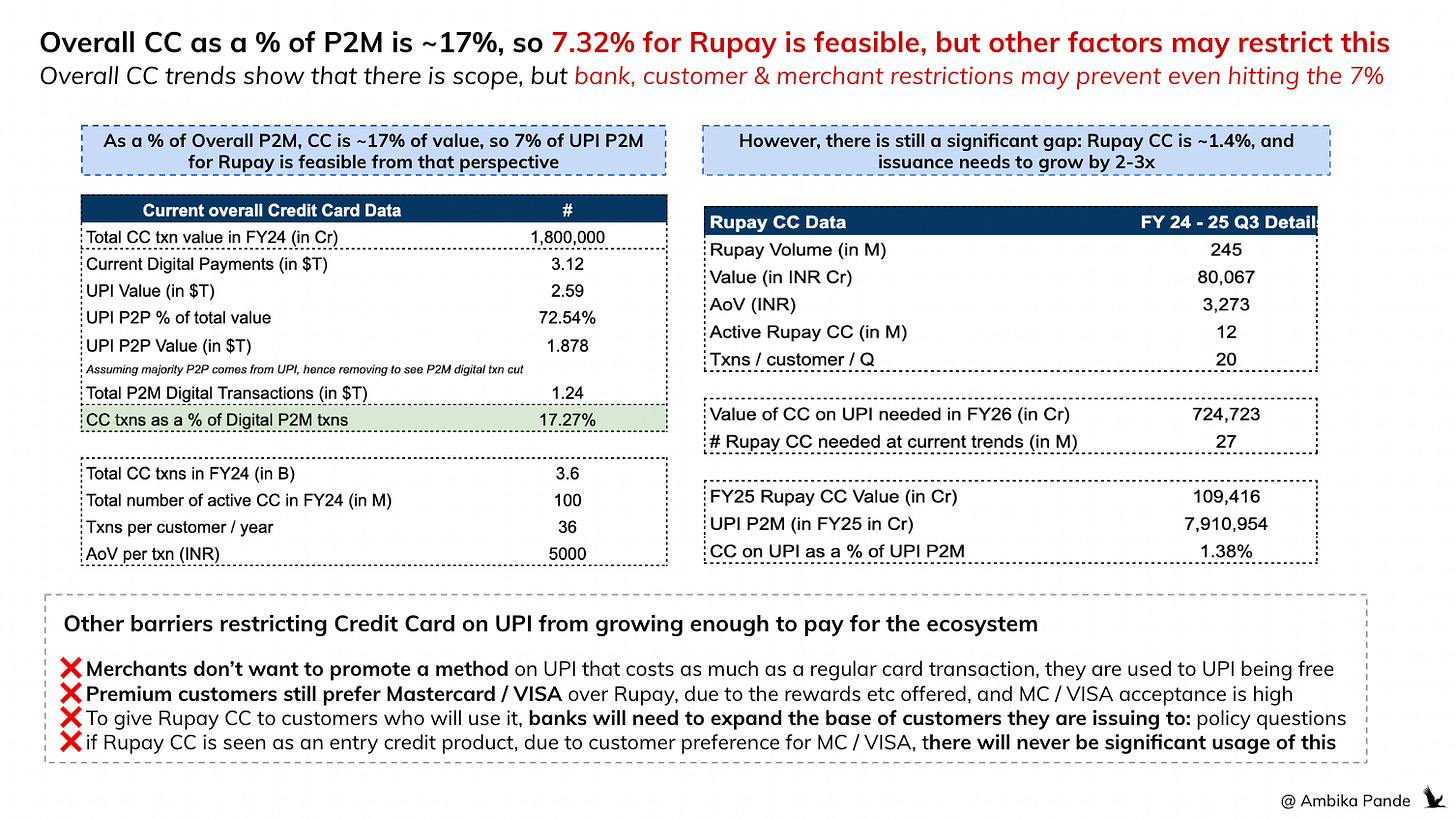

Overall, when I look at credit card volumes in India, and CC as a % of total P2M transactions, this is around 17%. So targeting a 7.32% for Rupay + Credit Lines on UPI is feasible theoretically. What will impact this is merchant and customer adoption, although with recent Credit Card launches by PhonePe and Gpay for Rupay on UPI, may signify that this is ready for takeoff. But only time will tell, and this is not time that fintechs may have.

So then, my takeaways are threefold:

If your core offering doesn’t make money, you’re in a tough spot. Cross-selling to a “free or near-free” base requires massive effort into other revenue streams, and it hasn’t been successful for players without scale.

If your core offering is built around free or near-free rails, it won’t make money: especially if you don’t own direct connectivity to the core rail. Example: in payments, only banks can connect to UPI rails.

If you’ve built something that requires banks to act (move money in UPI, share data in AA) and the bank isn’t making money, then you won’t make money either.

And that is why everyone is gravitating towards a few themes:

✅ The volume game (which gives leverage), but it's won. PhonePe, Paytm, GPay on B2C; Pine Labs and Razorpay on online and offline merchant sides.

✅ Wealth management, intrinsically profitable. Almost every wealth player is profitable: Angel One, Zerodha, Groww. There’s margin to go around, and opportunities to build for specific customer pockets, and product pockets mass middle, mid-to-low income, savings and investment (like Bachat), or FD / MF first such as Stablemoney, PowerUp.

✅ Go wherever the bank makes money. With margin compression in core DPI services, the strategy is to follow bank revenue. The major source: lending (interest income). That’s why we’re seeing a surge in lending and lending-adjacent fintechs: credit management systems, lending TSPs, alternate credit scores, etc.

The problem with “go wherever the bank makes money”: big banks have little incentive to move unless there’s value in lacs of crores, and smaller banks lack risk appetite.

It’s almost a catch-22:

For big banks, moving anything takes months, if not years. Heavily regulated, massive organizations, constrained by policy and opportunity size. For HDFC (₹346k Cr revenue FY25), would they make internal changes: new CMS/LMS for a credit product, or partner with a TSP, for a INR 1,000 Cr/month GMV lending opportunity? Revenue is single-digit % of that. While massive for lending TSPs/fintechs (Zestmoney and Axio were each doing INR 400 Cr/month at their peak), it’s a blip for a big bank.

For smaller banks: challenger banks like SFBs (AU SFB, Ujjivan SFB) or newer universal banks (IDFC First, Bandhan), this could be interesting. They have user bases of 2.6M (Ujjivan), 12M (AU SFB), to 35M (IDFC, Bandhan), which is one-tenth of established banks like HDFC (120M users). They want to grow and are willing to take more risk, partnering with TSPs and fintechs to acquire customers or merchants. But they can’t handle risk, and one big fraud case in credit or payments can wipe them out. In non-credit businesses, monetization is limited, and it’s a “loss leader” game. Even with the spiritual will to enter, the ability to fund losses is constrained.

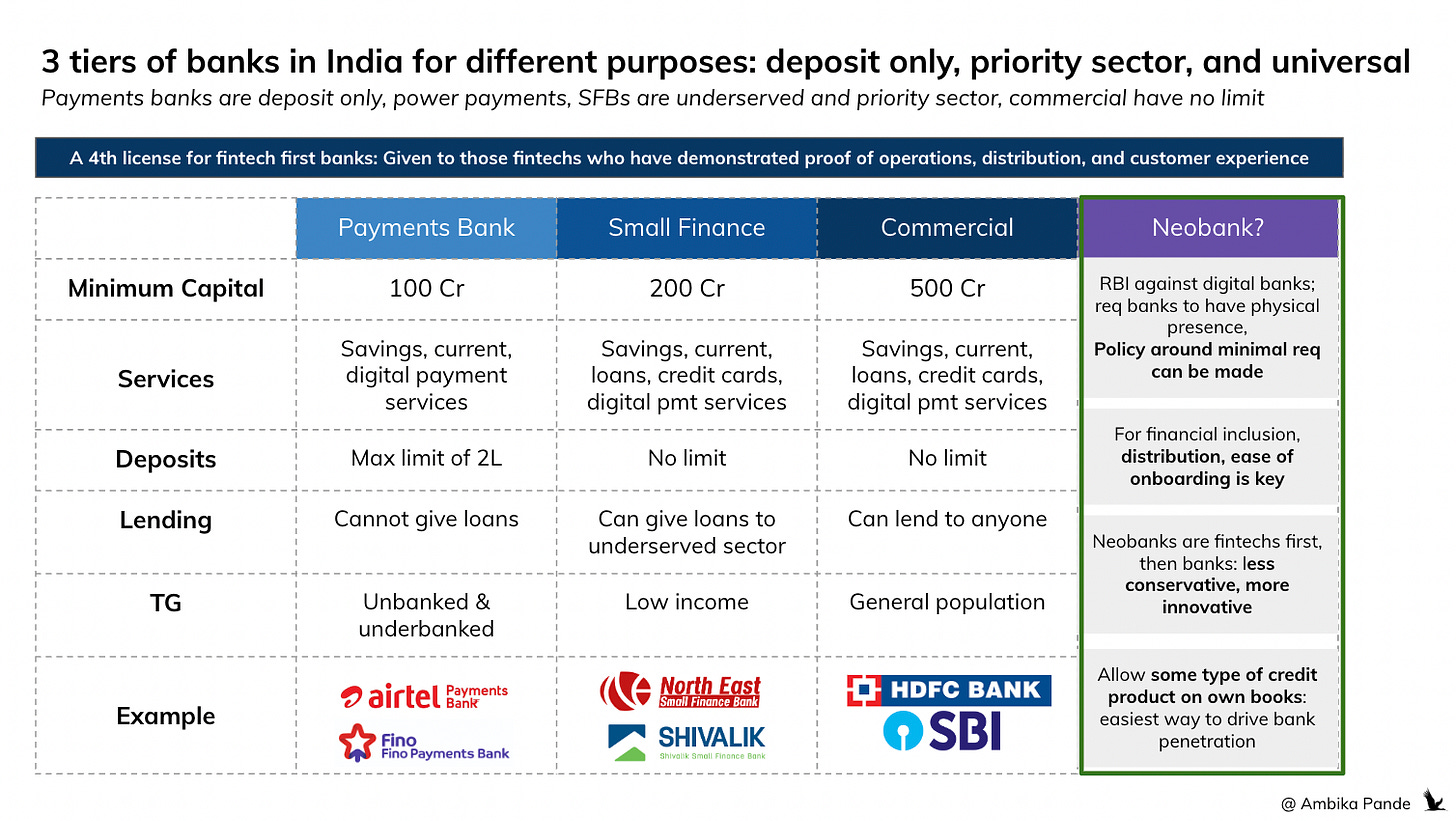

To solve for different types of products that require banking flows (payments, deposit only, credit) is why India introduced tiers of banks

Perhaps this is why India introduced tiered banking licenses: to solve for these exact constraints.

Payments banks, small finance banks, and universal banks, with each tier designed to match different risk appetites, capabilities, and business models. The idea: give players the right-sized playground to operate in, based on what they can handle and what the market needs.

But now, we’re seeing movement: payments banks want to become small finance banks, and small finance banks want to become universal banks. Why?

Monetization and profitability are capped at the lower tiers, and RBI’s FY25 banking report suggests this is intentional (you can read it here) If you can only take deposits, or must lend primarily to the priority sector (underserved - earlier 75%, now 60%), your ability to make money is constrained. This base is inherently riskier, with limited ability to take large ticket amounts or repay consistently.

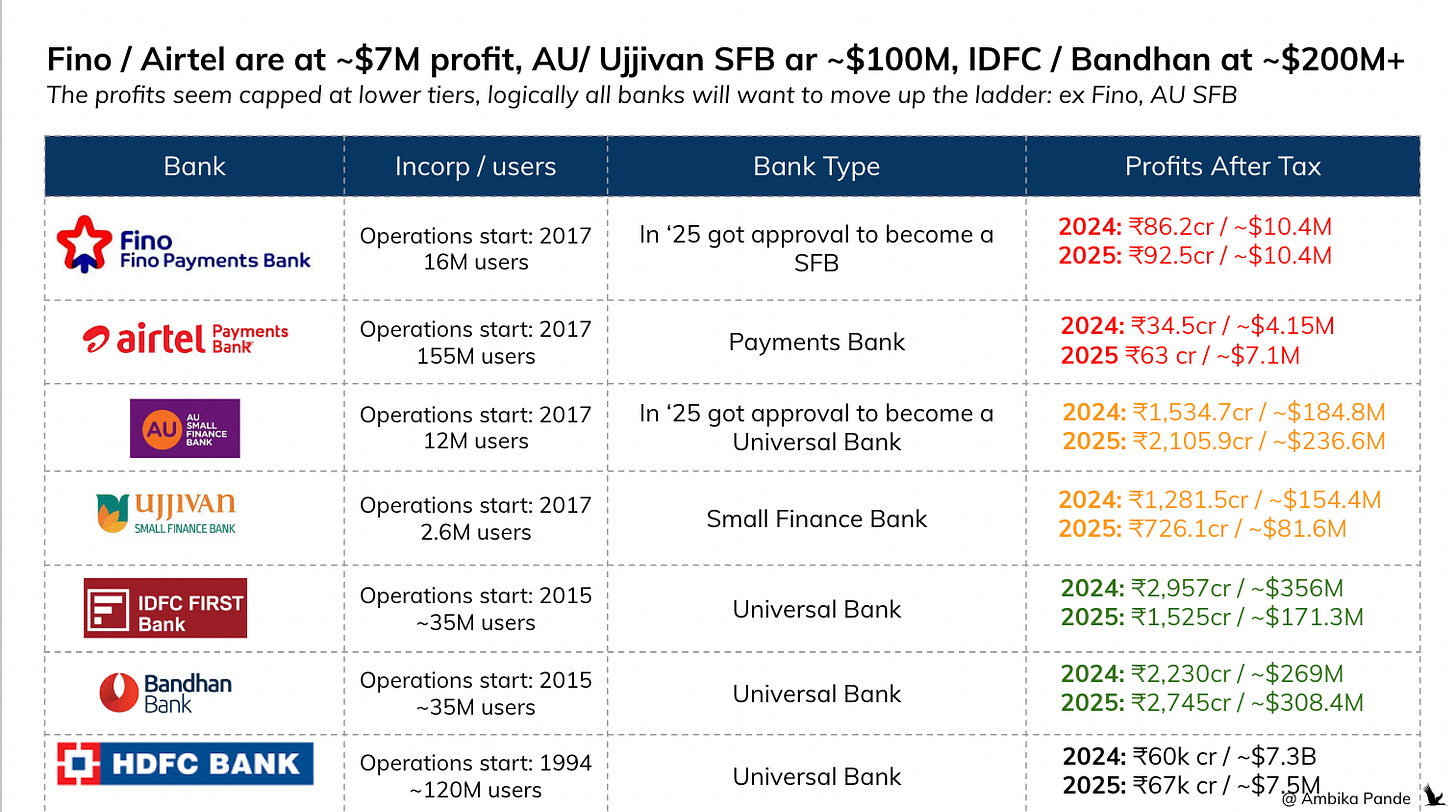

The numbers tell the story:

Payments Banks (Fino, Airtel) in FY25: $7-10M profit

Small Finance Banks (AU, Ujjivan) in FY25: ~$150M profit

Universal Banks (IDFC, Bandhan) in FY25: ~$250M profit

That’s a 10-20x difference.

And these banks all started operations around the same time: 2014-2017. Despite similar timelines, the difference in what they can/cannot do in lending and the inability to make money elsewhere is driving everyone up the chain. Fino wants to become an SFB. AU wants to become a universal bank.

Now, unless the government mandates a way for payments banks or SFBs to make money or provides some “extra” incentive for staying in that tier, everyone will move up the chain. It’s a pure business call. But even then, it doesn’t solve the underlying issues: improving operations and efficiency at banks, or enhancing their ability to take calculated risks.

And that’s where two things seem to be moving in the banking landscape in India.

1. RBI supporting FDI in PSU banks - it may improve operations, but only if management autonomy and performance linked incentives are addressed

Let’s dumb this down a little bit. RBI essentially wants to bring in foreign direct investment into Public Sector Banks. Why? Multiple reasons:

PSU banks in India are essentially your commercial banks in India, where the government holds > 50% stake. The key players here are your erstwhile State Bank of India (SBI), Punjab National Bank (PNB), Bank of Baroda (BoB), Canara Bank, Union Bank of India, Indian Bank, Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra, UCO Bank, Central Bank of India, Indian Overseas Bank, and Punjab & Sind Bank. They’re important because

They are known to have extensive presence, not just in your urban and metro areas, but also rural areas

They help implement government welfare schemes. Not that private banks don’t, but if the government does not have majority interest then it cannot drive this through private banks, it can only incentivize OR if they want to strong arm, then introduce bills or policy. But that is an extreme step

There is also a lot of trust that customers have in PSU banks. Since it is government backed, it is very unlikely to fail.

Now, the problem with PSU banks is that there is absolutely zero incentive for them to innovate, bring new products to the end customer, and take risks. Not that there is for private banks, unless there is profits to be made, but there, they are still profit minded. Take a minute and think about it. When you think of a PSU bank, what comes to mind? Extremely slow moving. Bureaucratic nightmare. Backward tech systems that take years to upgrade. Unwilling to adopt new technologies.

The hypothesis that RBI seems to be working with here is that FDI investment will help solve some of these issues. FDI then brings in more transparency, operational efficiency, and global best practices. The bank is then also judged against global comparables. Since there are significant foreign capitals, sharper questions are asked, less opacity, low margins are questioned.

And it’s not that PSUs are a stranger to this. This already exists. As of the March 2025 quarter, specific examples of foreign shareholding in major PSU banks include SBI (9.6%), Bank of Baroda (8.7%), and Canara Bank (11.9%).

A point to note here is that the FDI investment limit in India in PSU banks remains ~20%, and hence, if you see the above numbers, they don’t breach that limit, which are all ~10% or lower. In contrast, large individual FDI deals have primarily occurred in private sector banks, which have a higher FDI limit of up to 74%.

There has been market speculation and government consideration of raising the FDI limit for PSU banks to 49% to attract more capital, but the official limit remains 20%. In fact, we’ve seen a sharp drop in the market share of PSU banks ever since the government came out and clarified that right now there are no plans to increase this to 49%. So clearly, the view in the market is that increasing this limit to 49% somewhere will help. Whether that really is the case or not is anyone’s guess. In private banks, while the cap is 74%, most don’t exceed 55%. In fact, in the case of Yes Bank, and Axis bank, the FDI is ~45 - 48%, well below the 74% cap. But the point is, that there needs to be atleast 40-50% ownership allowed.

Now, I have a few things that I’m thinking about to unpack this FDI piece further, and what will actually drive better operations

Just because the Indian government is pro FDI doesn’t mean this will automatically make PSU operations more efficient.

1. First, the Indian government needs to increase the PSU cap to atleast 26%, and provide a path to majority investment.

26% ownership is the magic number for minority investors. It’s essentially the minimum amount of votes that are required to block / veto any major decisions, which usually require 75% consensus. Anything below that is not worth anyone’s time. And further: this needs to provide a path to full control. So, if FDI is capped at 20%, then you’re not going to get significant investment in PSU banks, instead foreign investors will focus on the private sector: an example is the Japanese holding group: MUFG taking 20% stake in Yes bank, and committing to bring this ownership up to ~25%. That isn’t happening in PSU banks.

Now, while minority foreign investment brings capital, market discipline, and global best practices, FDI investors care primarily about profits and dividends, not really day to day control. The government retains majority ownership and voting rights, protecting policy objectives. PSU banks, being backed by the state, are less likely to fail, making minority FDI a low risk tool to encourage transparency and governance improvements. And all this is fine: but taking a stake without having atleast veto rights is a bit concerning to any investor worth their salt.

I’d also look at this from another perspective: for the government, this is all capital tied up in the market. You can’t really use it. Instead, liquidating those positions will free up more capital for them, which then they can use for other purposes: maybe to revitalize smaller banks, infra related activities (God knows metro cities in India can use this, shoutout to Bangalore potholes).

They key point to note here is that FDI improves bank operations only when at least 2 of these 3 exist:

Management autonomy

Performance-linked incentives

Regulatory pressure or market discipline

FDI alone = insufficient. What RBI will have to do is give management autonomy to drive outcomes and make it worth their while. And then policy and regulations need to drive innovation and best practices. Look at the salary of the SBI bank chairman vs private banks. The SBI Chairman’s salary has increased, drawing INR 63.87 lakh in FY2025 (including basic pay, DA, and other components). This increased from INR 37L in 2023. In comparison, in FY2025, HDFC Bank CEO earned significantly more, with a total package around INR 12.08 crore (INR 3.09 Cr basic + allowances + bonus).

The second thing that seems to be happening is consolidation of smaller banks to give smaller banks a better ability to absorb shocks, and handle risk taking appetite.

This has happened to some extent: it is so that smaller, weaker banks have more leverage, and the ability to absorb shocks, so that they can take more risks. There are some new reforms being planned for the next year, you can check out the link here. But essentially, there is a focus on bank consolidation, both for PSUs, and RRBs (Regional Rural Bank, the policy being enforced is 1 state, 1 RRB)

Consolidation also increases the banks issuer base and market reach, lending and credit expansion capabilities, and profitability and operational scale, while smaller banks struggle with limited capital, technology, and talent, and consolidation allows economies of scale and operational efficiency.

However, there is also a risk here: that of too much consolidation, also consolidates power, and reduces options in the market. And we’ve seen consolidation in the market play out in a bad way in other sectors: With the streaming platforms: JioStar, Prime Video and Netflix, ads are running rampant. And, the less said the better about Indigo, in retaliation to less favourable policy decisions in the aviation sector, decided to hold the government and the country hostage, by not complying. So, RBI needs to be cognizant that this does NOT happen here.

So then, to improve efficiency and risk appetite, RBI is making moves:

The government recognizes banks are inefficient and wants to bring in FDI to fix this, but unless they increase the threshold to at least 26%, it won’t help much.

There’s focus on market consolidation to increase bank strength and improve governance, but it remains to be seen how they’ll protect against consolidation risks.

What is NOT solved: Incentives for banks to invest in certain revenue streams or innovation, and performance-linked incentives that would further drive this.

Now, add to this the facts I discussed earlier.

That fintechs have realized that unless they’re:

In a space where the bank also makes money, they also won’t, thus moving into credit products, with a focus on eventually becoming an NBFC, or in some cases, a bank (more in point 2).

Some fintechs have taken the leap to become banks themselves, versus just NBFCs for credit, to gain flexibility across operations—banks can also handle payment flows. That’s why Slice and BharatPe, despite having NBFCs for credit (BharatPe with Trillionloans, acquired controlling stake in 2023; Slice with Quadrillion Finance, acquired in 2019), also got SFB licenses, giving rise to Slice SFB and Unity SFB.

No incentives for banks operating in payments bank/TSP spaces or priority sector lending, and with profits being 1/10th, will naturally result in banks like Fino and AU SFB moving up the chain.

A fourth point, not specific to banks: while fintechs are tech-first and understand flows well, cracking lending and credit requires the right team. Lending is more than “solving for UX and workflows”-it’s about reducing cost of capital and managing NPAs. Team quality and experience matter enormously here.

So now, if I put all of this together, these are a few predictions I have with how this is going to evolve:

1. Private Banks will raise FDI, but PSU’s will only be able to attract serious investors if the below happens

No investor worth their salt will get in for a stake less than 26%, since that is what gives them control and veto power.

Management autonomy, and incentive linked compensation is introduced

There will also have to be incentive linked compensation to specific revenue streams, such as digital banking, maybe even DPI schemes, to promote investment and innovation

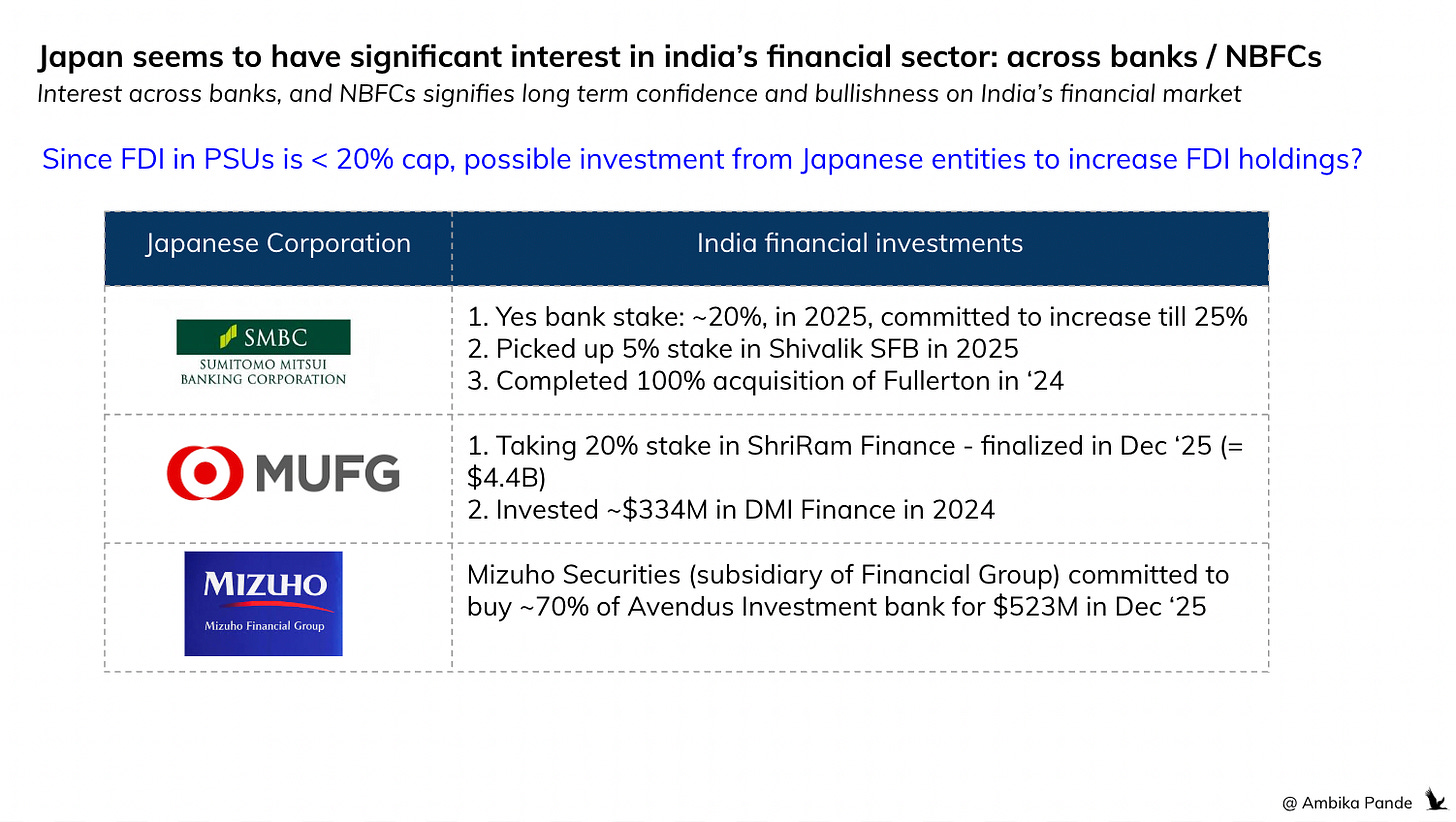

On a side note, there seems to be a lot of interest from Japan based corporations in India’s financial system.

I expect this trend of investment from Japan to continue, not just in banks, but in the Indian fintech landscape. This is a positive outlook on India’s credit and financial landscape. In fact, investors see a lot of synergies between Japan and India, in terms of tech innovation in the financial landscape, and both regions together are seen as a collective strategy in APAC.

SEA and MENA is obviously of interest as well, but Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia etc are still 5-10 years behind India in terms of fintech innovation, although favourable policies, especially around neobanks, and movement in the open banking space in this region suggests that this space is going to grow fast. An example of some financial investors driven by Japanese companies is below: SMDC, MUFG, and Mizuho are the key players, taking stakes in multiple financial entities in India.

2. Fintech banks will continue to move up the chain to become universal banks: both Slice SFB and Bharatpe - Unity SFB.

These banks probably see themselves more as “neobanks,” and not priority sector lenders, which is what a Small Finance Bank essentially is. It’s highly possible that consumer apps, and fintech with merchant distribution will go after banking licenses now.

Note: What is interesting is that this is NOT how RBI sees this. Basis RBI’s 2025 banking report (and you can check out the detailed report here), a lot of how they see banks in specific tiers as “specialized banks.” What RBI seems to be saying is that the system needs differentiated institutions, not clones of universal banks at smaller scale. But then, for that to happen, there have to be ways to make money apart from just lending, which requires pricing on DPI to come in, which isn’t the case as of today. This report also does acknowledge data fragmentation in banks, and hence the focus on ULI and AA frameworks for pulling data from different sources, and focus on risk management, and interoperable architecture, but doesn’t mandate anything internal to banks just yet, so this will take time to move. I had written in detail about this problem of data fragmentation in my article: #64 Innovation at the edges, stagnation at the core

The point being, that in absence of monetization strategy, this has started happening, EVEN in regions where infra monetization exists, so it’s only a matter of time before it happens in India: Example: Paypal in the US applied for a banking charter. I see it further breaking into two categories:

👉 Consumer apps going after banking licenses, and eventually becoming universal banks.

Priority sector lending as we’ve seen doesn’t really help with revenues. And these are fintechs, which means, they want to operate as neobanks, which means that they want to be able to do everything that they can. In fact, RBI’s 2019 SFB regulations set a path for exactly this. The minimum requirements for a SFB to become a universal bank is the following.

5 years of successful operations as SFB

Listed on stock exchanges

Net worth ≥ INR 1,000 crore

CRAR consistently above regulatory minimum (CRAR = Capital to Risk-Weighted Assets Ratio)

GNPA & NNPA under control (Gross NPA and Net NPA). Usually this means GNPA is < 4%, and NNPA is ~1.5%.

Proven governance, compliance, and risk management

No supervisory concerns from RBI

BharatPe - Unity SFB commenced operations in November 2021. Slice - SFB rebranding completed in 2025, although North East SFB (that Slice merged with) has been operating since 2016. Now, Bharatpe in 2025 announced that it was targeting an IPO in 2026. Slice in 2025 announced that it is gearing up for an IPO in 3-4 years.

Both these timelines coincide with ~5 years of operations as a SFB, and in the case of Slice, from the date it rebranded. So clearly both of these are going for the universal bank play, and will try to become the “neobank” model that India sorely lacks today. And maybe that is why there is also a lot of investment interest around your small finance banks - Shivalik SF bank for example, raised funds from investors that include Accel and Lightspeed. I assume the vision here is for it to turn into a universal bank, in light of the profit limitation on SFBs. I expect this to continue to happen for SFBs, especially those with serious investment raised - all eyes on SFBs such as Jana, Suryoday (RBI approved 1729 Capital - an FPI, to acquire upto 9.99% stake in it in December ‘25) , Equitas SFB and so on.

👉 Merchant / tech players will go after payment bank licenses, purely to support the tech stack play.

There will be interest from fintechs to acquire / merge with banks, across the board. Not just on the B2C side, but on the B2B side as well: Protean acquiring a 4.95% stake in NSDL payments bank. Now, there are two ways this can go:

Your B2B / tech fintechs may decide that going after a payments bank is easier to support their core business of building tech stacks rather than lending. But even if this is the short term vision, there is nothing a payments bank can do, that a SFB, or a universal bank can’t.

Movement here may start off from a payments bank perspective, but more up the chain. And unless there is a change in revenue making opportunities, or incentives to the lower tiered banks, there will continue to be movement to everyone become a universal bank: this is for payments + SFB, and for fintechs, which will go from payments → SFB → Universal Banks

As the market undergoes a “re-bundling” of sorts, in the next few years, we will see consolidation happening, not just at the fintech, but at a bank - fintech level, Airtel Payments Bank being a prime candidate

Airtel Payments Bank has massive scale for a payments bank. It has reportedly ~155M users, and is in the top 10 in 3 out of the 4 legs of UPI payments. It made FY25 revenues of $7M on this 155M user base. AU SFB in contrast made revenues of ~$81M in FY25, on a 12M user base.

However, it should be noted that Airtel is a telecom provider with ~35% market share in India, and a large part of its user base can be attributed to some cross sell initiatives; reportedly 400M in India have Airtel SIMs, which rationalizes this 155M number. I had written a piece some time ago on the intersection of fintech and telecom, and you can check it out here: #53 Neobanks, eSims. and Telecom: the rise of sticky financial ecosystems.

The one leg that Airtel Payments Bank isn’t in the top 10, is the remitter leg, which is the customer bank, suggesting that despite its big base, a lot of its customers are not digitally savvy, and thus doing only UPI payments or mobile banking. And of course, despite having a 10x greater user base, Airtel Payments Bank revenues are < 10% of AU SFB. Food for thought.

Payments banks like these could be prime candidates to be the focus of some consolidation efforts as fintechs scale, and want to own part of the bank.

It is possible that with Slice and BharatPe paving the way, consumer apps with scale become prime candidates to go get banking licenses of their own, such as what a PayPal in the US has done.

PayPal in the US, despite the scale and volume it has, processing ~25B transactions every day, has applied to get a bank charter expand small business lending and offer savings accounts, reducing third-party reliance and gaining FDIC insurance for deposits. While PayPal is more B2B focused, this seems to set the stage for “fintech-banks,” both B2B and B2C focused, paving the way for the new wave of banks in this sector.

Credits:

A special thanks to Atul Pande for his invaluable insights on the banking and financial landscape in India.