[#74] Do all roads in fintech lead to license aggregation? (Part 6): Multi-license fintechs are driving profits and IPOs

India’s single PA license limits smaller players, while UK & Singapore use tiered licensing. Standalone players have razor thin margins, it's the multi-license fintechs driving profitability & IPOs.

Hi folks, and welcome back to this edition of: Do all roads in fintech lead to license aggregation?

You can check out the earlier editions in this series here:

Part 2: [#37] Having multiple licenses as an Indian fintech seems to be key

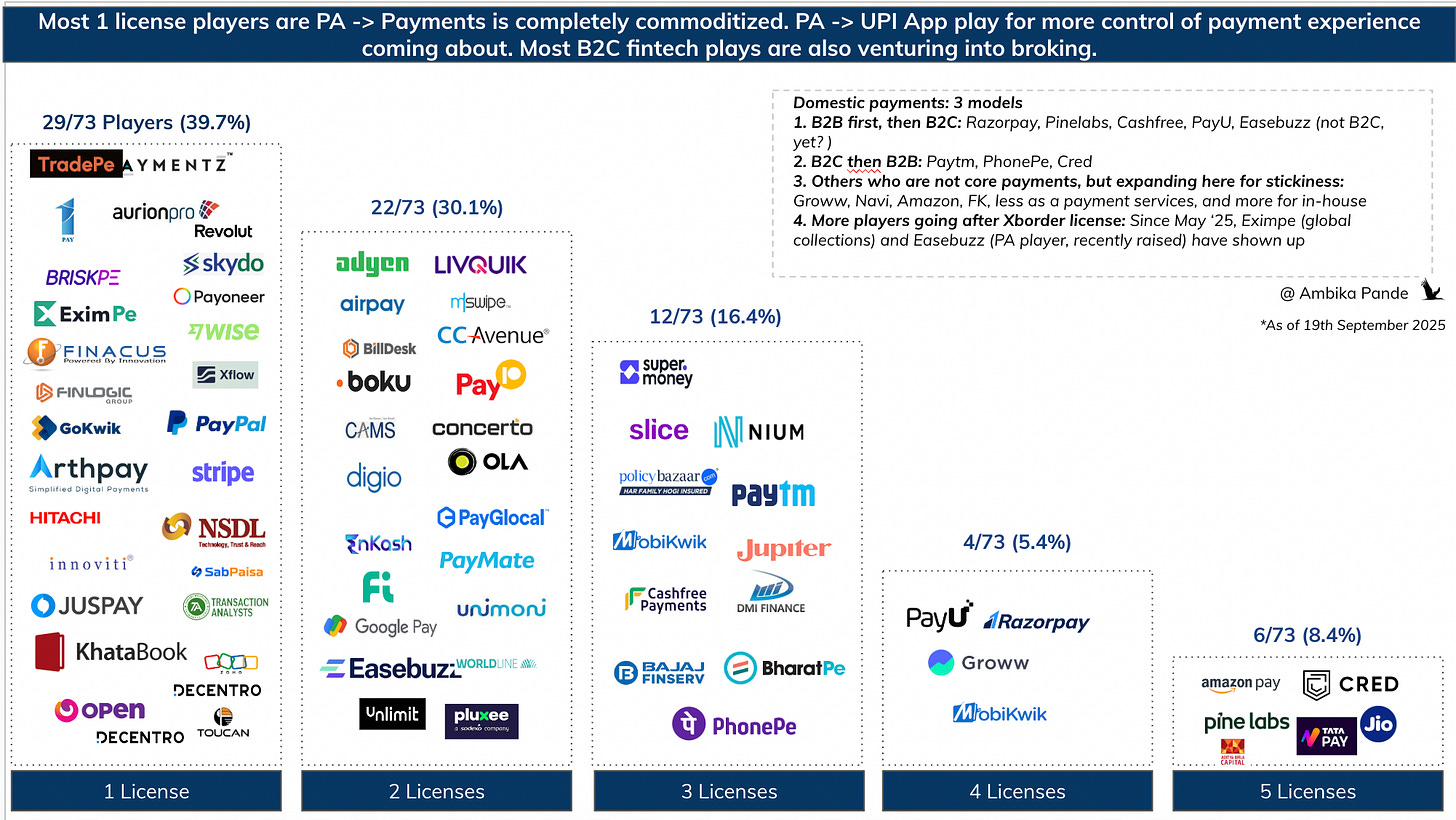

Part 3: [#54] There are very few “1 license players anymore” - PA seems to be the most popular

Part 4: [#63] It’s not just about license aggregation, it’s about stack specialization

Part 5: [#69] Payments is just the first step in going full stack

If you’ll notice, what I’ve tried to do is constantly track the ever evolving fintech landscape in India, and see if there are trends that can be spotted, which can provide some insight into the future of this space, not just through current data, but through data trends over months. I wrote the first edition of this back in August 2024, and a year later there is a lot that has evolved.

But first: let’s look at the updates from July 2025

A quick snapshot of what’s happened since the July update - which was the Part 5 edition:

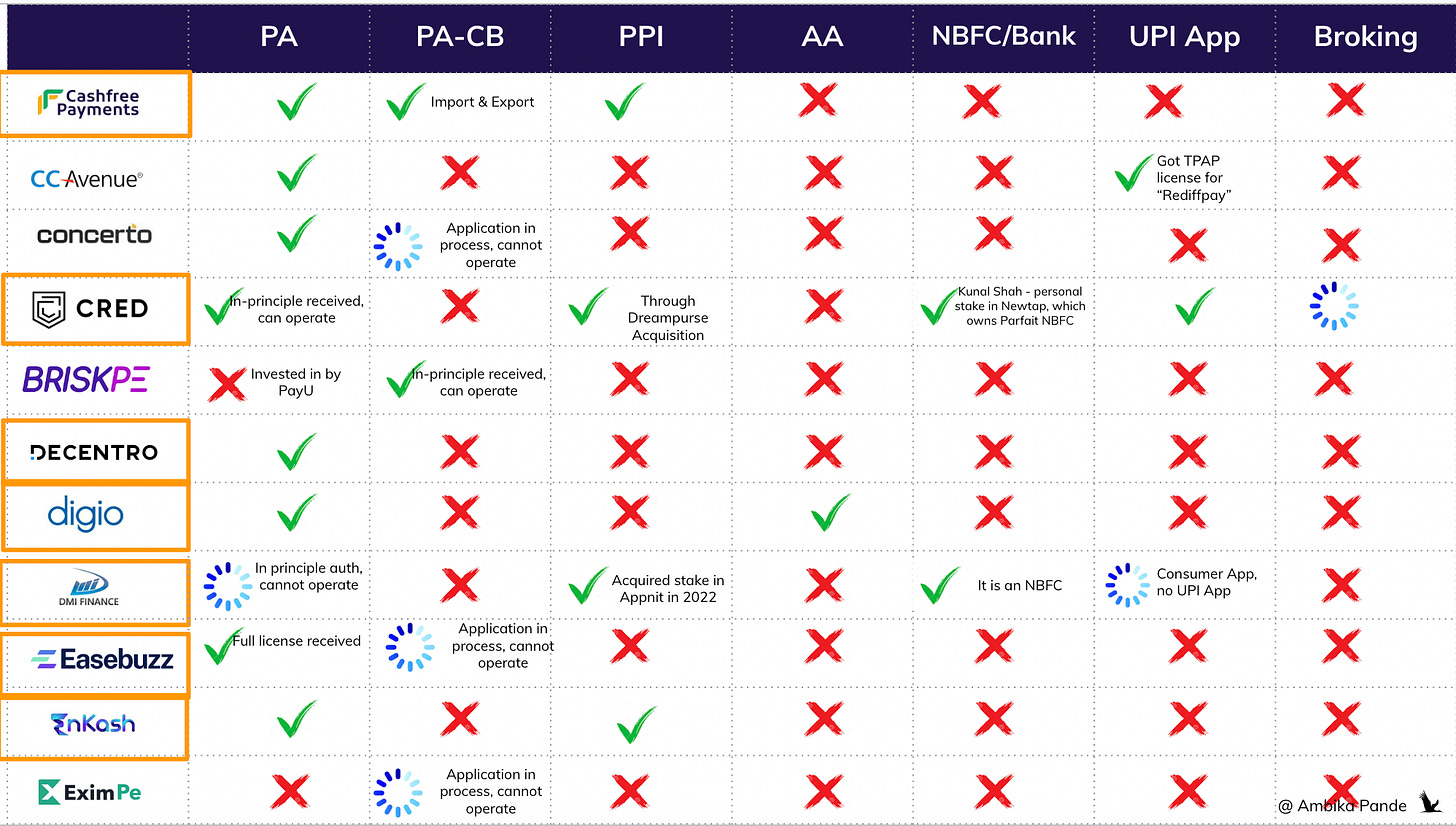

Blackbuck picked up a PPI license in July 2025.

ABFL, DMI Finance (Appnit) and Policybazaar (PB Pay) - all moved from “PA application in process” to “in-principle authorisation” this year.

PayPal upgraded from “application in process” to in-principle approval for a PA-CB.

Easebuzz is trying to get to scale in cross-border, now partnering with Xflow while its own PA-CB application is still in process.

No notable new players getting into this space. It seems like fintech in India, atleast when you look at it from “players in the market” perspective is saturated, and it is now existing players which are getting their license status updated - this is in terms of PA licensing, and possibly UPI App certification. Where I do expect new players to come in is on the PA-CB side, for cross border money flow, and on the NBFC side, as more consumer & merchant facing fintechs want to get into the lucrative business of lending on their own books.

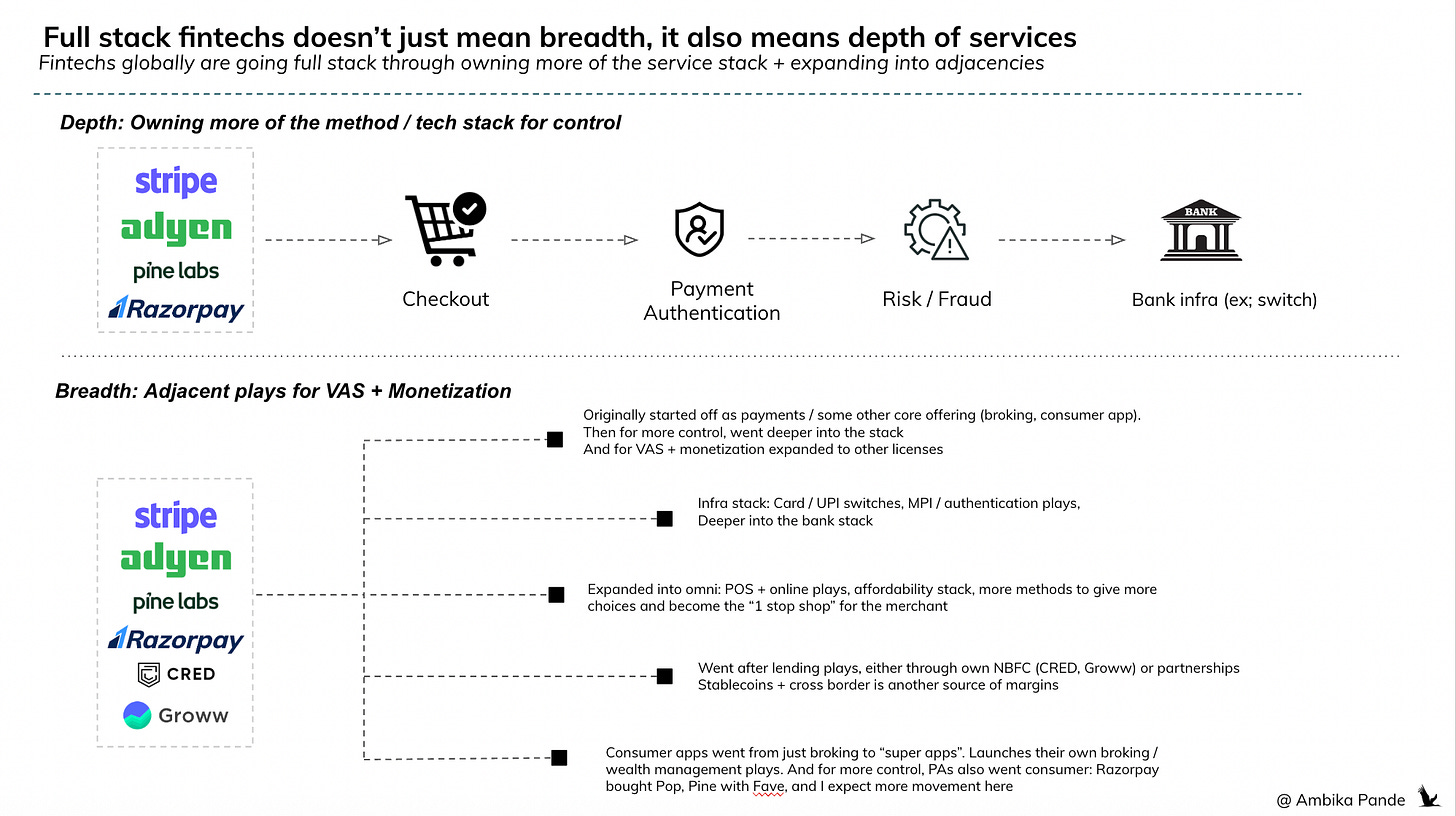

What has come out quite clearly as I’ve tracked this space, that becoming a full stack fintech is where the table stakes lie now. This is what enables players to 1) give themselves optionality and also 2) have the most control over the stack to boost success / approval rates, or whatever the core metric of that offering is.

The way I’ve tried to define it is that there are two kinds of full stack: Going deeper into the method is one AND going wider into different offerings is the other

✅ Owning the method stack - with the bank infra, switches and so on

In UPI: not just integrating with banks, but running your own switch, building a UPI app, and owning the payee/payor side.

In cards: not just routing transactions, but going deeper into authentication — tokenisation, MPI, DS, 3DS rails, basically owning the OTP verification & authentication step. And obviously other methods as well, I’ve just used cards & UPI as an example as the most popular types of payment methods (not counting affordability)

In both cases, it’s about performance. The less you rely on third parties, the tighter your control on latency, debugging, uptime, the better your chance to win merchant volumes. And since many merchants are using payment orchestrators, that route basis performance, even a few bps in success and latency matters.

✅ Owning the license stack

This is the more strategic play. PA-CB, NBFC, broking, UPI app certification - each unlocks a new adjacency.

Slice with its SF bank. BharatPe with Unity. Paytm with broking, PA, UPI.

And newer plays like Cashfree going deep into cross-border with import/export PA-CB licenses.

The logic is simple: payments margins in India are a few basis points at best. Profitability lives in cross-border flows and credit. Banks are still doing the heavy lifting, but fintechs are layering on distribution, UX, and speed. The optionality of licenses is what gives them room to build adjacencies that actually move the needle.

One truth has become clearer over the last 12 months: just doing domestic payments in India will not make you a sustainable business. The future belongs to players that build full-stack infra + licenses, and then branch into lending, wealth, and cross-border.

Let’s take a quick look at some of the payment players currently in the market, and what they’re doing

1. Easebuzz: going international

Easebuzz is one of the few standalone PAs still pushing hard. They applied for a PA-CB license earlier this year, and raised a $30M round in April ’25 led by Bessemer, largely to fund their move offline (QR, POS, etc.).

On paper, they look solid: FY25 revenue of ~INR 650 Cr, net profit of INR 25 Cr, and $30B in GTV. But here’s the interesting bit: INR 650 Cr on $30B in GTV works out to ~25 bps. That feels too high for net revenue in payments.

Here’s why:

In cards, the issuing bank keeps ~1.5%, networks ~0.2%, acquiring banks ~0.2%. That 0.2% is split between the PA, orchestrators, switches, etc.

In UPI (60%+ of PA volumes), there’s effectively no MDR.

Which means a PA’s net revenue usually sits at just a fraction of that 0.2%. It’s actually even less due to the UPI weightage

So for Easebuzz to show a ~25 bps take rate, two possibilities:

This is gross revenue (i.e. counting the full MDR before payouts). In gross revenue, the entire 2% is counted as revenue. In net revenue, this is the actual amount that the PA keeps AFTER paying everyone, and handling kickbacks etc, which is a fraction of a fraction: some x% of 0.2%. By this logic, this ~25 bps take rate seems pretty high. So there are probably two things that could happen here:

They’ve found a niche or product play that lets them charge above-market (unlikely in such a commoditized space) OR this is the gross revenue. (I’m assuming net revenue would be ~50% of gross, but either way Easebuzz is profitable).

Either way, credit to them for reporting profitability. But expanding into offline infra is going to pressure margins further. And their tie-up with Xflow for international settlements shows the direction of travel: standalone domestic payments isn’t enough, so you expand into new licenses and adjacencies.

That’s the recurring theme we keep seeing: the pie in domestic payments is just too small - so players move into cross-border, credit, or adjacencies that need a license.

PhonePe started out as a UPI app, but quickly realized that being just a UPI app wasn’t enough. Over time, it layered payments, broking, PPI, and is now a market leader in UPI with ~46% share. Unlike some peers, it hasn’t aggressively chased a PA-CB license for international flows - the domestic “super-app” story is what works for it.

On the IPO front, PhonePe is one of the big fintechs (alongside Groww) expected to list in 2026. Originally, it was planning a $10 - 12B valuation, roughly in line with its last funding round ($12B). But recent Inc42 reports suggest the IPO may come in lower, at $7-8B.

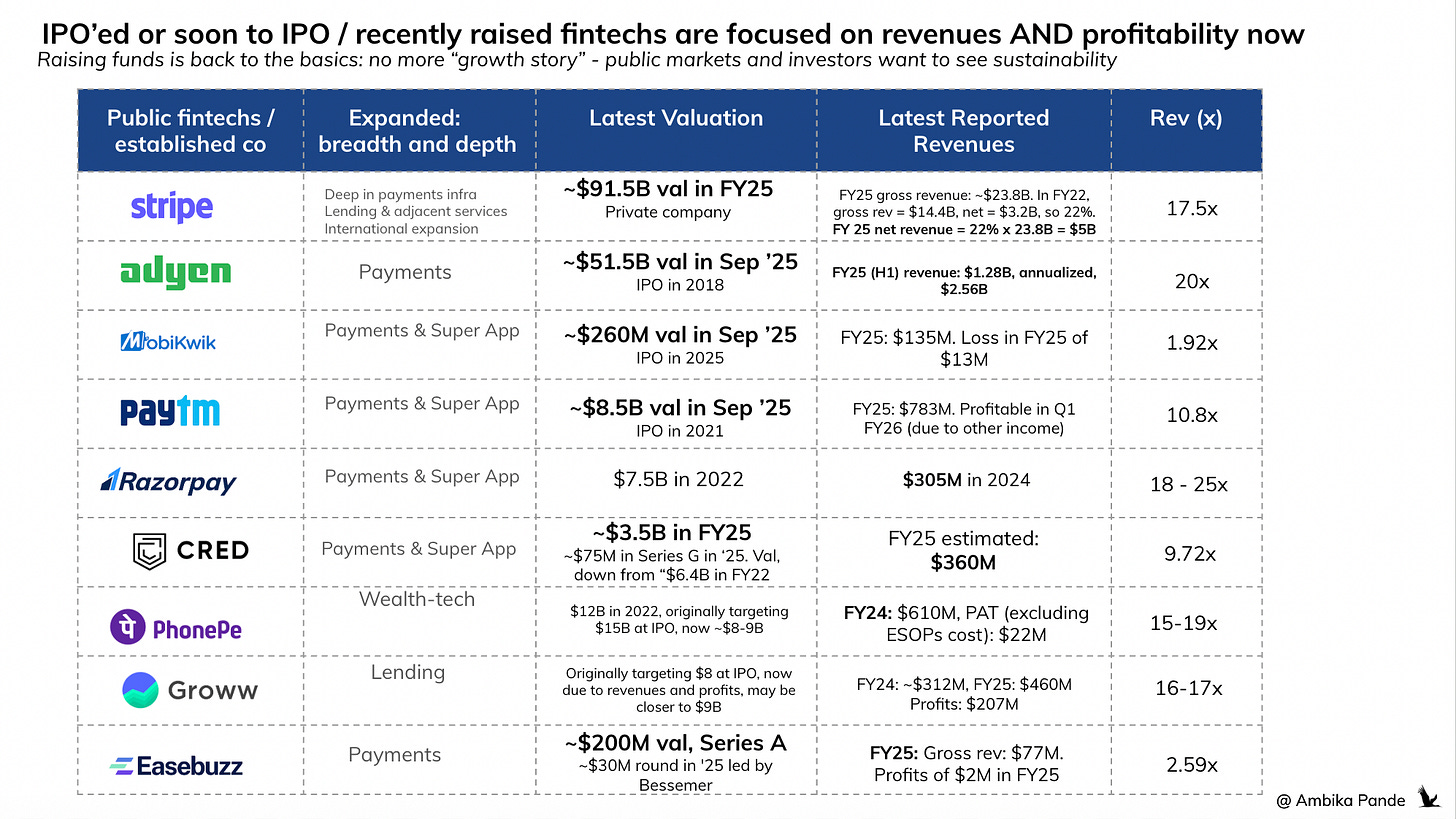

In FY24, PhonePe reported revenues of INR 5,064 Cr (~$600M), a 74% jump over FY23. If you assume a 50% increase into FY25, revenues land around $900M. At a $15B valuation, that’s ~16x revenue multiple.

For context:

Adyen trades closer to 20x revenues.

Block (Square + Cash App) trades at ~5–6x.

So if PhonePe’s numbers are net revenues, the math checks out - it sits somewhere between Razorpay and Adyen on multiples. But if they’re gross, then the effective multiple is much higher, and the IPO looks stretched.

Adyen’s net revenue multiple is ~20x currently (~$51.5B valuation in June ‘25, and FY25 H1 NET revenues $1.28B, and annualized at $2.56B.

Stripe’s FY25 valuation is $91.5B, but its FY25 revenue isn’t publicly disclosed, so I’ve estimated it based on past metrics.In FY22, Stripe processed $817B in TPV and earned $14.4B in gross revenue (~1.7% of TPV), with net revenue of $3.2B (~22% of gross). Assuming FY24 TPV was ~$1.4T, applying the same 1.7% gives ~$23.8B in gross revenue. At a 22% net take rate, that implies ~$5.24B in net revenue. This puts Stripe’s valuation at:

17.5x net revenue multiple ($91.5B / $5.24B)

3.8x gross revenue multiple ($91.5B / $23.8B)

This net vs. gross revenue multiple is key when comparing Stripe to Indian fintechs and assessing relative valuation. From a benchmark perspective, this is where I’d ideally benchmark other major fintech players in India, especially since we’ve now established that cross border is where the revenue are, and eventually everyone will go international. Which they have already done.

Paytm: International ambitions, domestic rebuild

Paytm has been back in the news for the right reasons. Headlines celebrated its consolidated net profit of INR 122 Cr in Q1 FY26 – its first since September ’24, when the one-off sale of Paytm Insider to Zomato (~$243M) briefly pushed it into the black.

On the surface, this looks like a comeback story: revenue is up 28% YoY and contribution profit is up 52% YoY compared to Q1 FY25, reflecting tighter cost control and stronger lending flows. But there’s nuance in the numbers. Paytm’s EBITDA in Q1 FY26 was INR 72 Cr, and after finance, depreciation and amortization costs of ~INR 170 Cr, the company actually ran a net loss. What flipped the bottom line into a “net profit” was INR 241 Cr in other income, mainly interest from tax refunds – a one-time, non-operational gain.

So while operations are improving, Paytm isn’t yet sustainably profitable.

On the regulatory side, Paytm has restarted merchant onboarding with an in-principle PA (online) license approval, but it has notably not gone after a PA-CB (cross-border) yet. That’s interesting, given its international ambitions. In FY25, Paytm picked up a 25% stake in Brazilian fintech Dinie for $1M – a small ticket, but a clear signal it wants to understand the LATAM ecosystem. I’d read this as a strategic learning exercise before any large-scale move.

Once Paytm stabilizes its domestic stack (including the eventual re-compliance of Paytm Payments Bank), I’d expect them to chase the PA-CB license. Even if they don’t plan to run a fully-fledged cross-border money movement business, the RBI’s posture has been consistent: if you touch cross-border flows in any way, you need to be licensed.

Pine Labs: IPO on the horizon

Pine Labs is another payments market leader now gearing up for its IPO. The company reported a profit of INR 45 Cr in FY25, with revenues growing ~25% to reach ~INR 1,735 Cr. Its IPO push suggests that it is consolidating its scale in India, while showcasing its international presence (Southeast Asia being the key geography). The profitability milestone in FY25 signals that its playbook of diversified merchant services is working

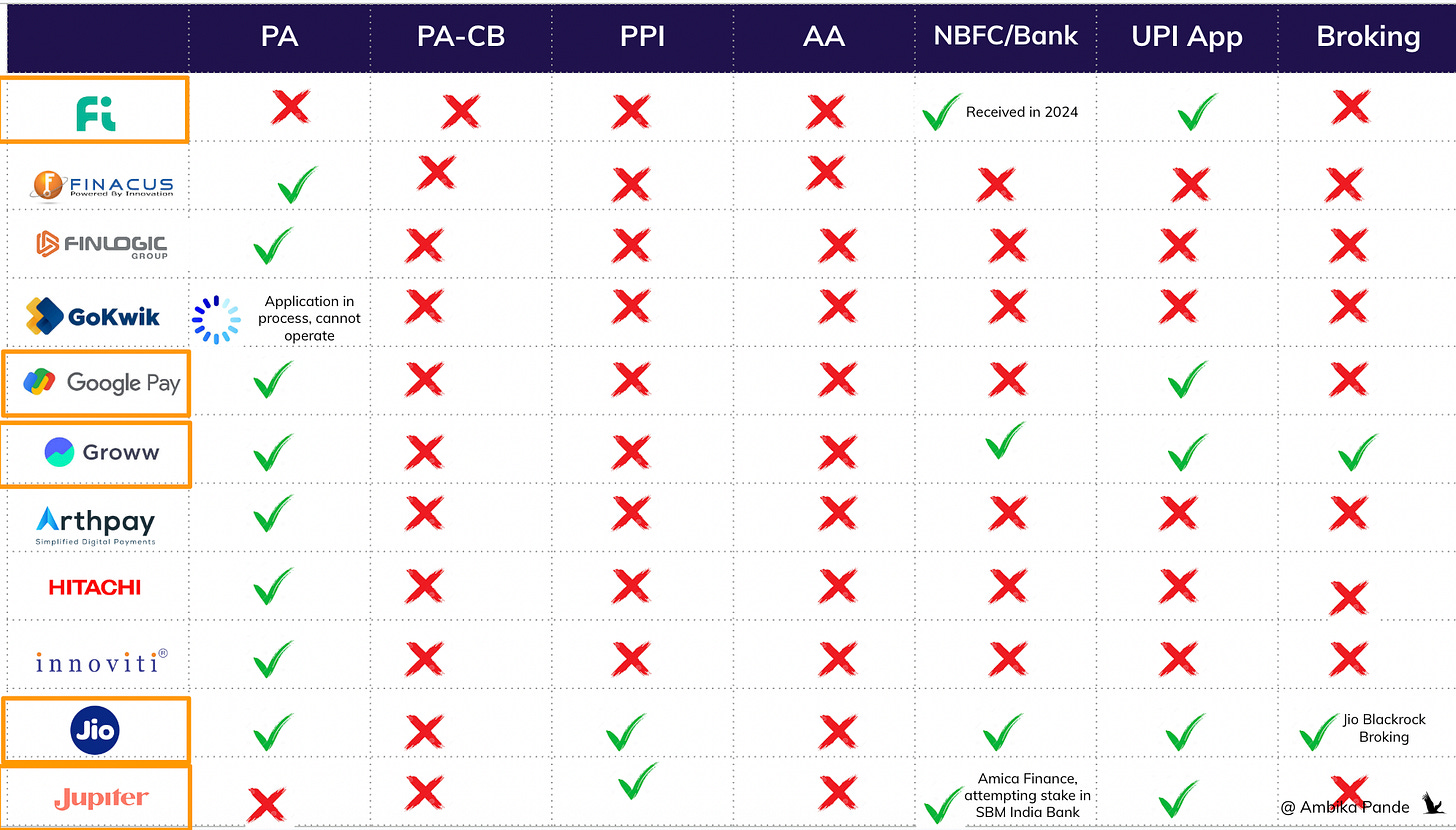

Groww: stockbroking + UPI + licenses

Groww isn’t a payments player in the traditional sense. It’s first and foremost a stockbroker, and a dominant one at that. It recently filed its updated DRHP, with an IPO expected soon. Originally, Groww was targeting a $7–8B valuation, but its FY25 numbers may justify a higher figure: revenues of INR 4,056 Cr ($460+M) and net profits of ~INR 1,824 ($207M) Cr.

On the consumer side, Groww has built a base of 13-15M active users. While its core is stockbroking and investments, it has also quietly become a UPI app, clocking ~INR 9,000 Cr in monthly transaction value as of August 2025 (which is ~$1B). This is not insignificant - for context, challenger UPI apps like Navi and Super.money are in the same ballpark.

From a licensing perspective, Groww now has:

NBFC - likely tied to its LAS (loans against securities) product. It has built a respectable loan book here, and this also ties into its long-term lending play.

PA license - while Groww may never want to operate as a “classic PA,” the fact that its UPI flows are growing means it makes sense to be regulated here. If you’re doing INR 9,000 Cr/month in UPI volumes through an entity, RBI would prefer you to hold a PA license rather than just piggybacking off someone else

Deep dive on some of the past valuation pieces I’ve written are below:

But the point is: the natural path for fintech expansion is to first go deep (owning more of the method stack), then go wide (adding adjacent licenses and services), and eventually international.

That’s exactly what we’re seeing: Paytm, Razorpay, Pine Labs - all of them have either invested abroad or set up international offices. And of course with Easebuzz, while it is waiting for its PA-CB, has tied up with Xflow for powering cross border money flow. And Cashfree of course - with it’s import and export PA-CB, PA, and PPI. There are two takeaways I have from the above section:

But the bigger takeaway is this: standalone domestic payments will not work. The margins are too thin, the pie too small. You can’t survive on just UPI or card acquiring. You need breadth, lending, broking, cross-border, banking licenses to make the model sustainable. So atleast for those payment aggregators which are just on PA, especially with the gaming & rent payments ban, they will need to open up other streams of revenue

Second, and equally important: profitability is back in focus. Unlike Paytm, which IPO’ed while still loss-making, there’s now a clear shift. Investors are rewarding profitability over just scale.

Easebuzz is profitable, reportedly $2M in FY25 (INR 22 Cr)

PhonePe is profitable (excluding ESOPs cost) at $22M in FY24 (INR 194 Cr)

Pine Labs reported FY25 profits of $5M (INR 45 Cr)

BharatPe reported its first ever PAT of $68k (~INR 6 Cr) is lining up a pre-IPO round of ~INR 1,000 Cr, valuing the company at 11-12x revenue multiples

Groww is profitable and consistently so with FY25 profits of ~$207M, AND with a massive user base and diversified revenue streams.

The world makes sense again - it’s not just about chasing GTV anymore, it’s about proving that the model works and can stand on its own. AND, all the above players are diversifying: Easebuzz is PA & PA-CB, PhonePe is UPI App, PA, PPI and broking, BharatPe is UPI App, PA, NBFC, and Unity Small Finance Bank after the centrum merger.

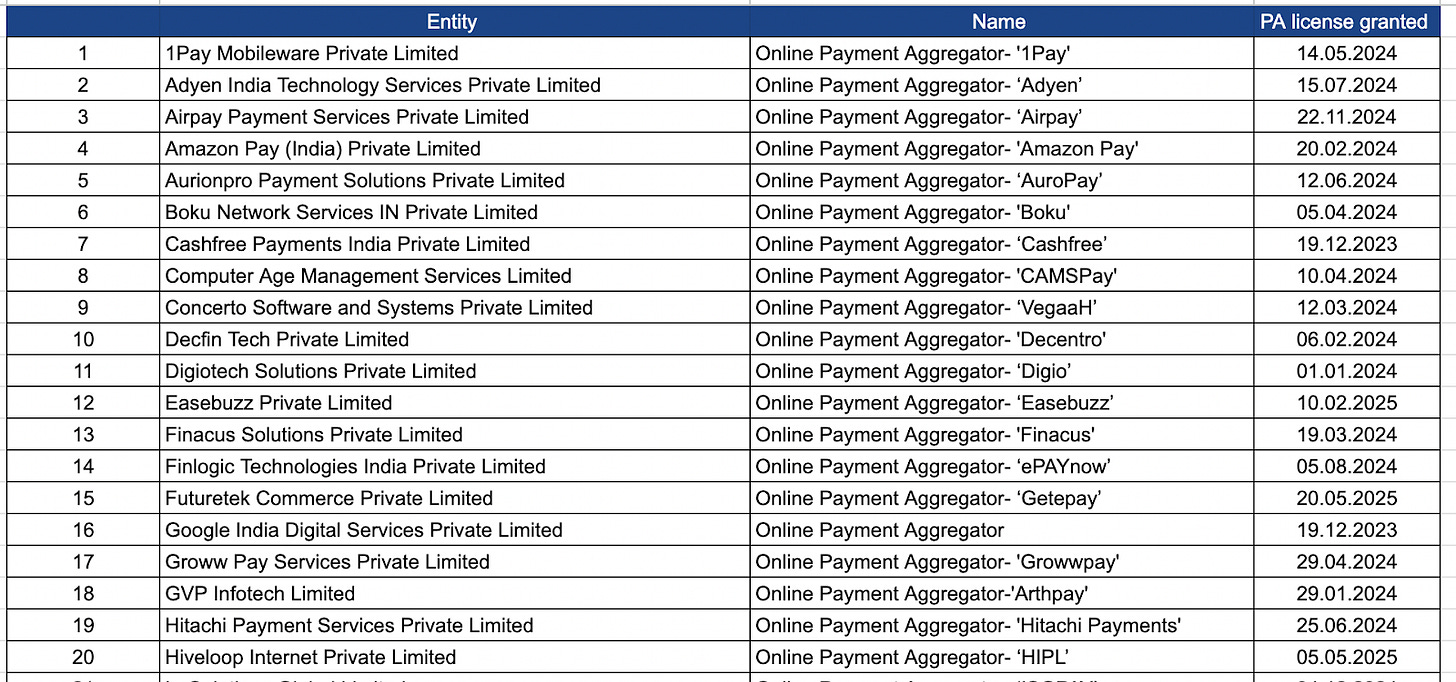

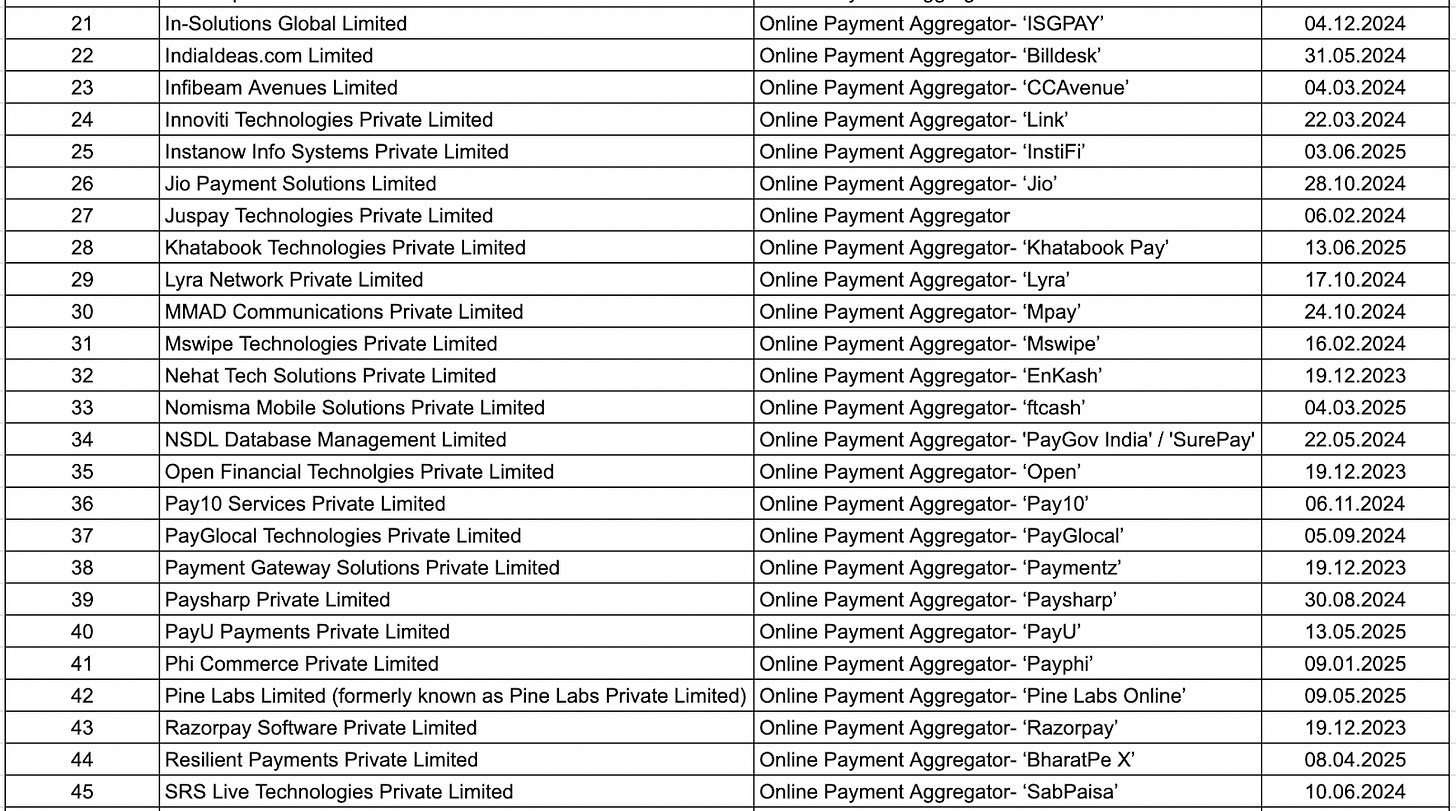

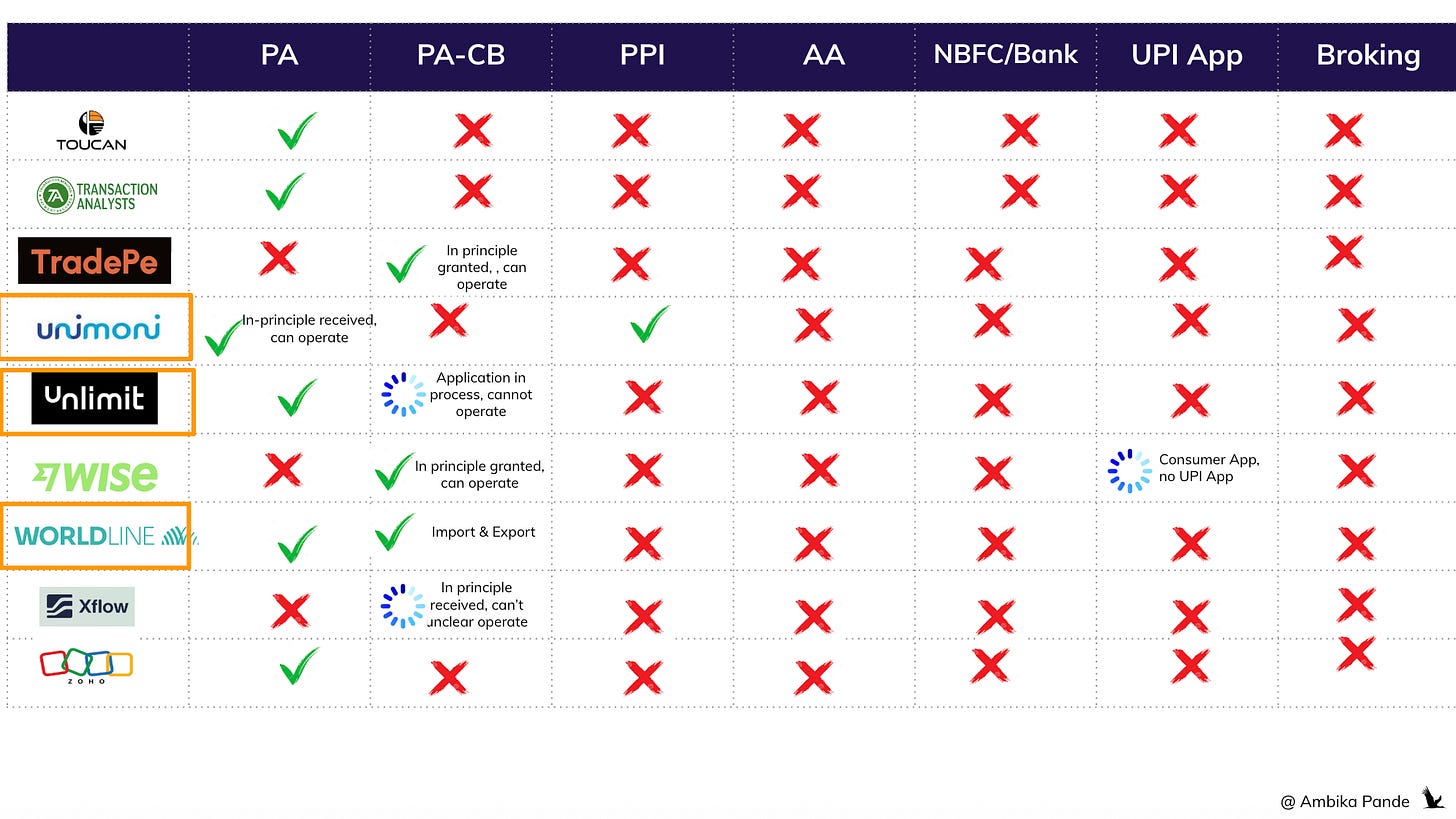

Now also, look at the set of players that now hold a PA license → it is a crazy number: 55!

They come in all shapes and sizes - and interestingly, many of them aren’t traditional payment aggregators at all. A good chunk are UPI apps. And there seem to be WAY more than makes sense: if 4-5 players in the market are profitable (and barely so), it seems to say that there is no more room for sustainable businesses to exist - and no one here is dumb, folks understand the market mechanics and the saturation levels.

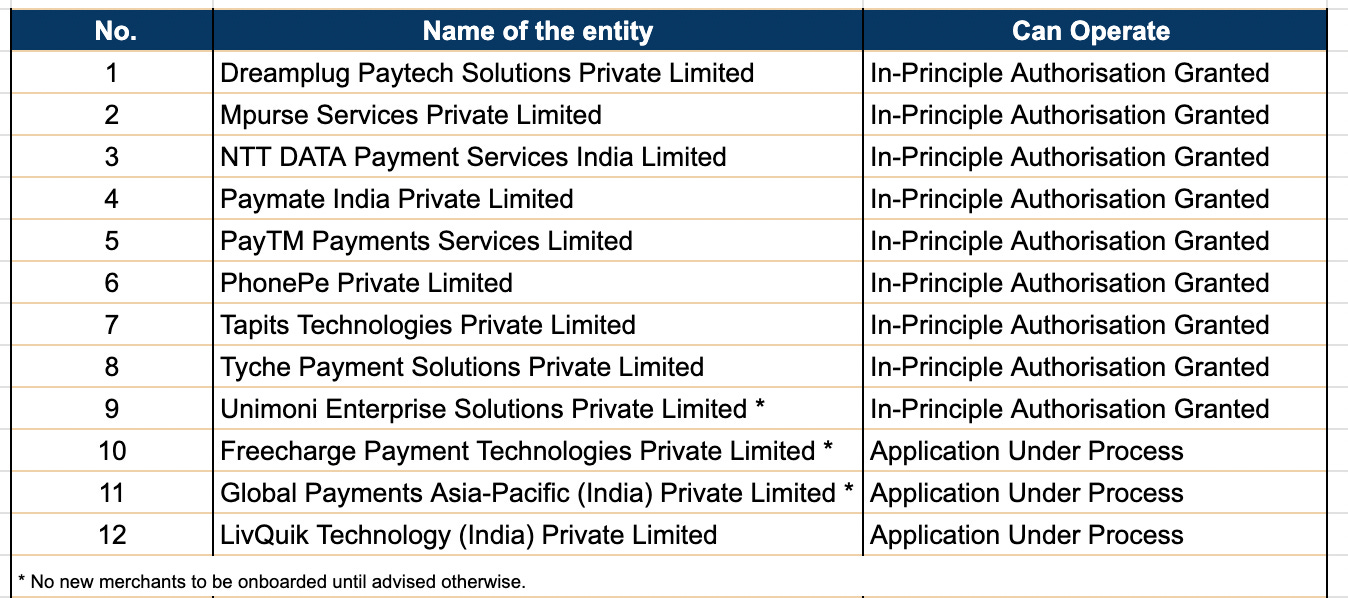

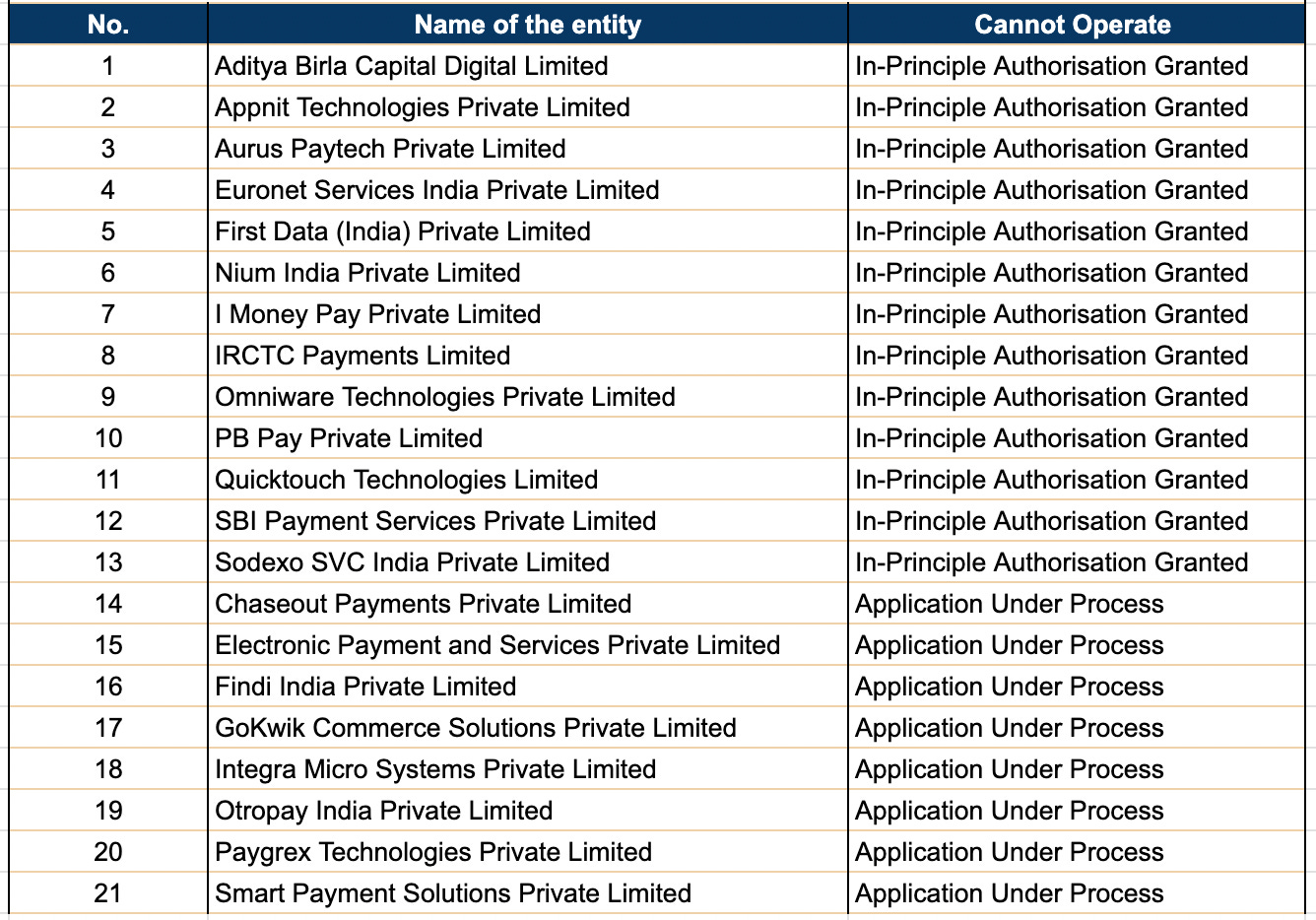

The numbers show how crowded it already is: 55 players are fully certified PAs, 12 more in principle approval and 21 cannot operate, but have a license in stage of approval

👉 55 players with full licenses below

👉 12 players which can operate as a PA, and have a license in some stage of approval

👉 21 players which cannot operate as a PA, but have a license in some stage of approval

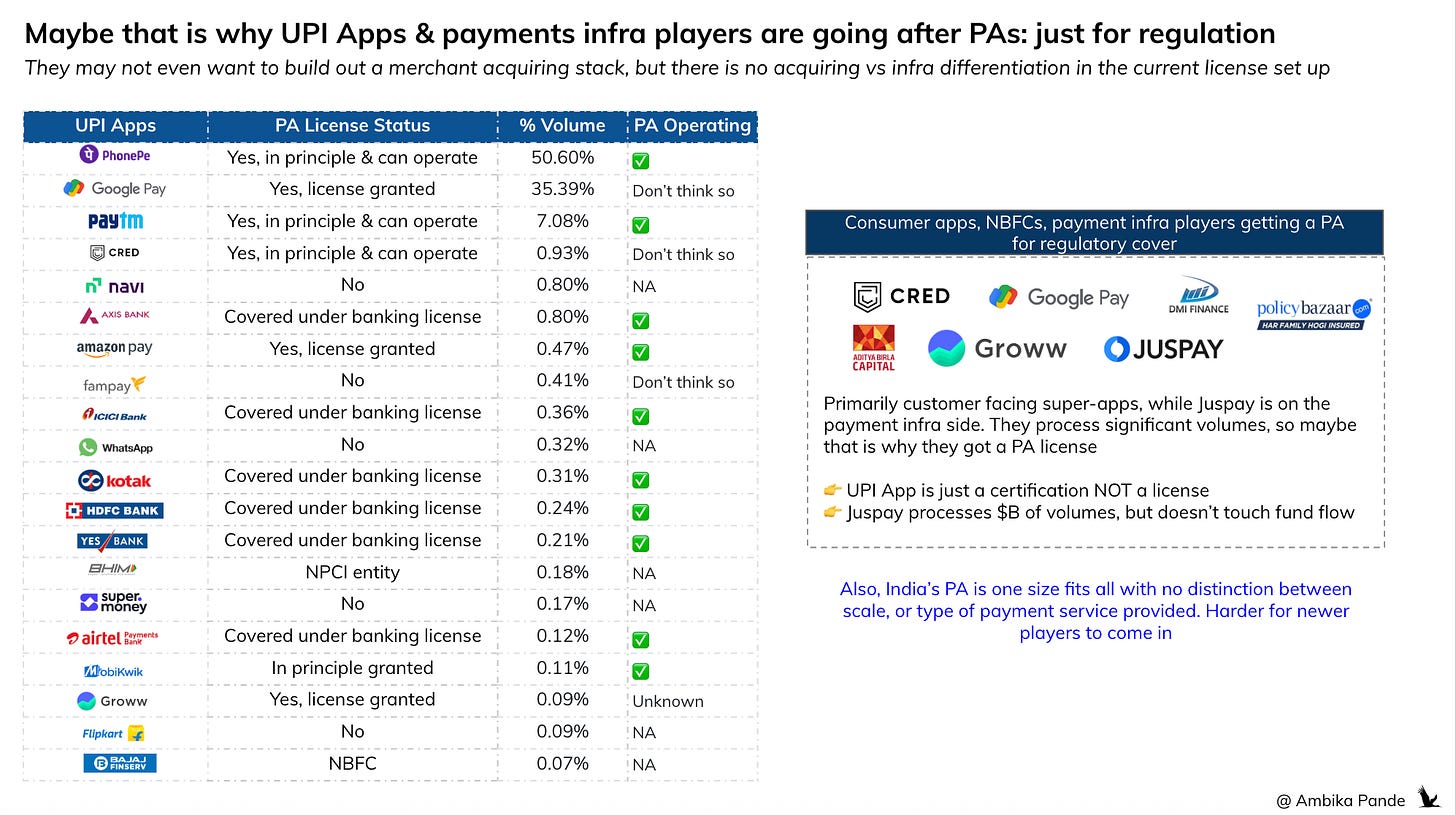

Makes no sense. But here’s my view: majority probably don’t even plan to operate as PA’s → they’ve got this license for regulatory cover since they are in the payment space, and in India atleast there isn’t any other license that gives regulatory cover to payment players apart from the Payment Aggregator license

Here’s the catch: most of these players who’s gotten a PA license probably don’t intend to build full-fledged aggregation businesses. Instead, they’ve picked up the PA license as a regulatory hedge.

The point is: even if you’re “just” a UPI app, or an infra player who doesn’t want to be a full-fledged aggregator, you’re still touching money flows. UPI apps process volumes, they route payments, they sit in the middle. At some point, the RBI is going to look at that and ask: how are unregulated players playing such a central role in money flows? After all, being a UPI app is technically just a certification, not a license.

That’s where the idea of a “willingness to comply” license comes in. Something fintechs can hold to show they’re regulated, even if their core business isn’t merchant acquiring. It’s less about strategic economics, more about legitimacy and regulatory cover.

This is probably what’s driving NBFCs like DMI and ABFL, or even players like Policybazaar with PB Pay, to pick up PA licenses. NBFCs don’t make their margin in payments, they make it in credit. But holding a PA license is a way of being inside RBI’s perimeter, if they have payment / payment adjacent ambitions in UPI / affordability or something else. Same with Policybazaar: they already run a consumer-facing app, and may want to be closer to fintech or payment flows.

It’s also Gokwik, Juspay, and pretty much any UPI app that touches a transaction. So don’t be surprised if everyone ends up applying for one.

With UPI being the backbone of Indian payments, and RBI keeping a close eye on the ecosystem, holding a PA license gives them optionality. If tomorrow regulation tightens around who can operate or monetize on UPI, these players already have a seat at the table.

In other words, the PA license isn’t just about running merchant acquiring - it’s increasingly about future proofing.

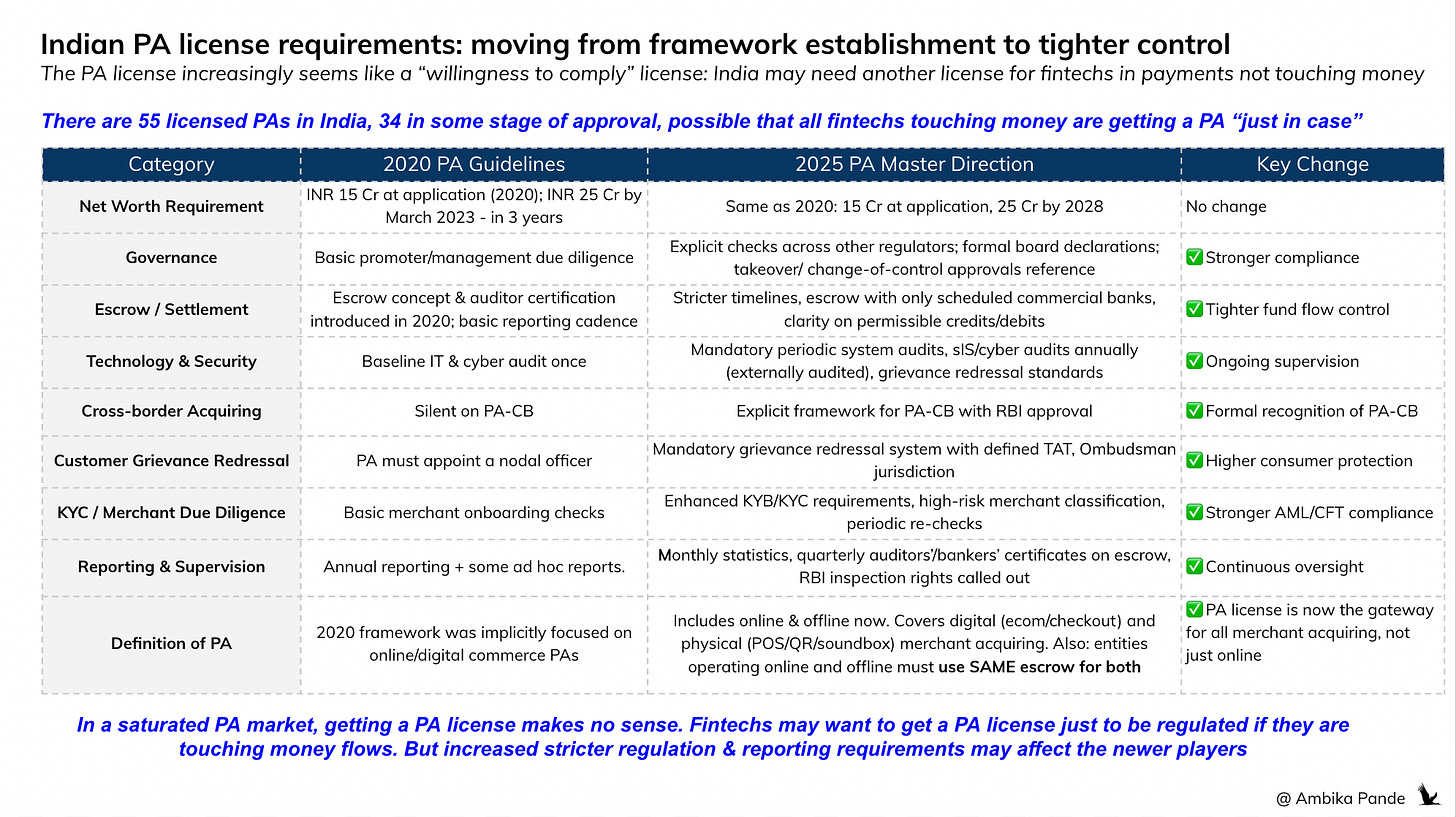

But here’s another problem with that: while in 2020 India’s PA regulations were to establish a framework, the updated guidelines of September 2025 have instituted tighter controls, which may make it tough for smaller / newer players in the payment / payment adjacent space

Ideally, there should be some difference in reporting, net worth, or KYC needs basis scale OR type of service offered. Payment aggregation ideally should only refer to those players that are touching / handling money flows. You’ve got a whole lot of other players doing payment initiation, or orchestration, and are involved in making the payment flow more smooth, without actually being involved in the fund flow. But in the absence of that, the PA license is all we’ve got. (And this is also where things blew up I feel, like in the case of Juspay, where after Juspay got the license, PA’s banded together and said that they would remove support for Juspay’s payment orchestration solution since they felt Juspay would steal their customers away. If there was another payment infra license, maybe this would have helped assuage fears)

Side note: Some points to note in the updated PA license requirements of September 2025

Tighter governance checks

Stricter controls on escrow accounts

More security / audit requirements on IT and systems

Stronger grievance redressal systems

Enhanced KYC / KYB checks

From annual reporting to monthly / quarterly reports & audits

And finally: while the 2020 PA guidelines only talked about online / ecomm players, the 2025 guidelines also brings in offline, POS, soundbox under these guidelines. Also - and this is interesting, the guidelines mandate that there has to be a single escrow used for funds for those players that operate as PA-O (online) and PA-P (offline). I guess RBI’s goal was to reduce arbitrage, and increase transparency, for unified settlement and monitoring. I’m assuming what happened in the past is that players operating in both online and offline, by maintaining two separate escrows were able to get around some net worth, KYC and reporting requirements, and maybe even cover up gaps in one account due to excess funds in another.

TLDR: Suddenly this makes getting a PA license as a hedge a lot of additional overhead, and cost of compliance that a smaller fintech may just not have the capability to manage

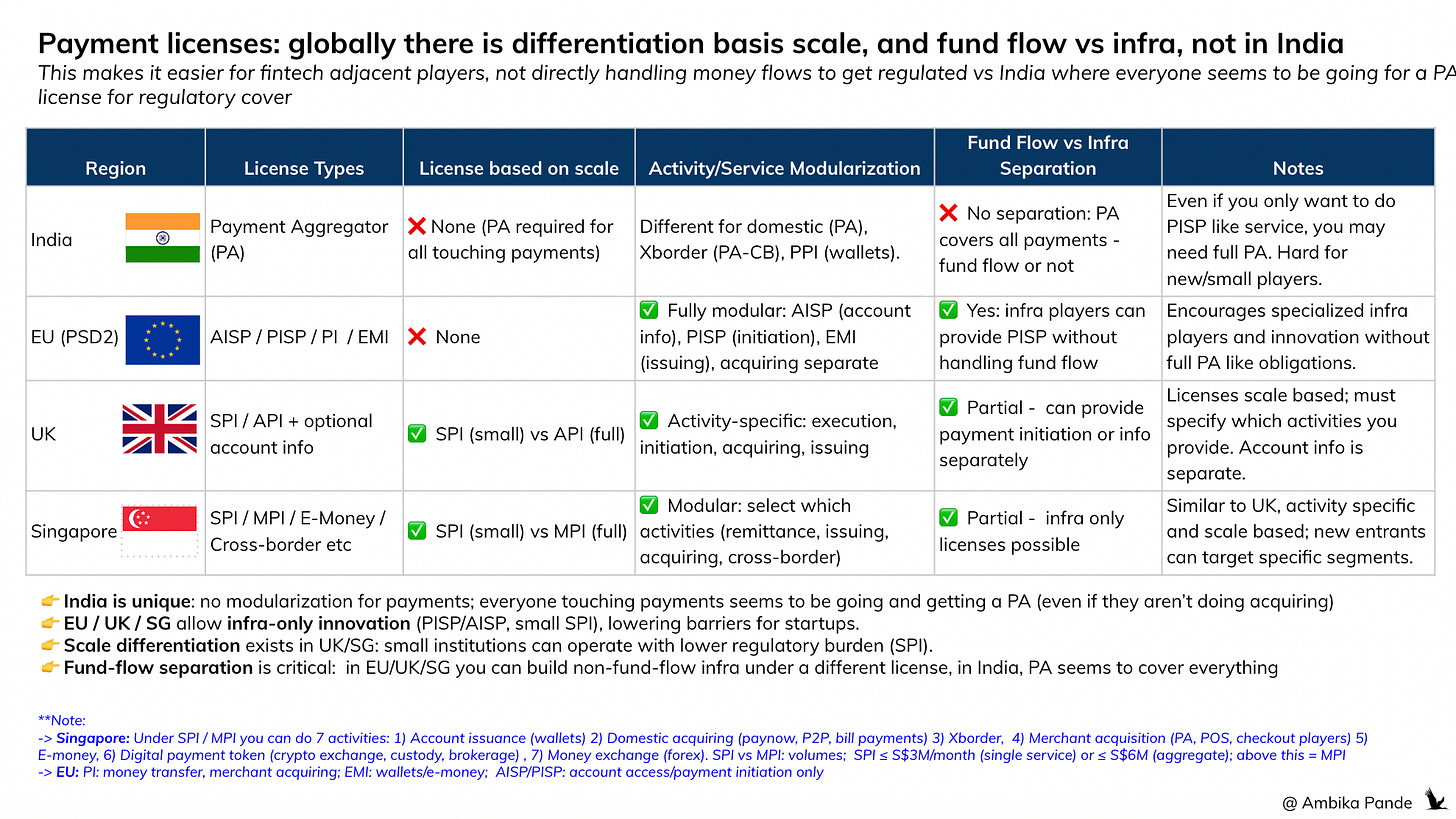

Regulators elsewhere have created light-touch, perimeter-expansion licenses keeping this exact problem in mind:

✅ Singapore:

In Singapore, MAS offers a Major Payment Institution license and a Standard Payment Institution license, so even small players can operate under regulation without the full compliance burden. And SPI & MPI is differentiated basis the scale they have: volumes: SPI ≤ S$3M/month (single service) or ≤ S$6M (aggregate); above this = MPI. SPI’s & MPIs can conduct the same activities.

Account issuance (wallets)

Domestic acquiring (paynow, P2P, bill payments)

Xborder remittances

Merchant acquisition (PA, POS, checkout players)

E-money

Digital payment token (crypto exchange, custody, brokerage)

Money exchange (forex)

Capital requirement:

SPI: $100k

MPI: $250k

Point to note here is that players have to apply for SPI / MPI + the specific service (ex: Wise has MPI + Xborder). It’s not that one just applies for a SPI / MPI and then can operate all the above activities

👉 TLDR: SPI has less capital requirement, lighter touch, fewer disclosures required → which best for early stage players.

✅ EU

4 licenses:

PI: money transfer, merchant acquiring. Closest to India’s PA license

EMI: wallets/e-money

AISP: Account initiation Service provider - kind of like access to customer data (like India’s Account Aggregators)

PISP: Payment initiation only, not touching the fund flow

👉 Allows for separate licenses for infra players (AISP / PISP). PI is equivalent to India’s PA license, but it has further broken down acquiring into AISP (which is like India’s AA for data access) and PISP, which is payment initiation (like Juspay). Unlike in India where everyone in payments needs to get a PA license, EU has broken down where payment players actually move money, and where they are just involved in the transaction without actually holding any funds

✅ UK

Similar to EU with scale based licensing, and the fund flow vs just payment infra distinction. SPI (Small Payment Institution), API (Authorized Payment Institution), AISP (for aggregating account information) and PISP (for payment initiation). And then of course the EMI (Electronic Money Institution) for prepaid accounts / wallets issuance.

Min capital requirement:

SPI: Initial capital not required (source)

MPI: ~$25k

So the key themes coming out here from these global examples are:

Licenses are modular: you can choose what you do (initiation, info, acquiring, issuing), it’s not 1 blanket license that you have to get regardless of fund flow involvement or not, like India

Scale differentiation exists in some regions (UK, Singapore): SPI vs MPI (or API in the case of UK), enabling ease of licensing for smaller players, which helps to drive innovation by smaller players

Infrastructure players can operate without touching full payments (ex: EU PISP).

India has an all in one approach for payments

India doesn’t yet have this middle layer. The PA license has effectively become that “catch all” option for payment fintechs to show willingness to comply. Which is why you’ll continue to see not just aggregators, but NBFCs, brokers, and even consumer apps quietly filing for one.

Payment Aggregator (PA) license seems to be required for almost all players in payments, regardless of them touching fund flow. Even if it is not stated explicitly, this does seem to be the way it is being interpreted. Even if you just want to initiate payments or provide “payment infra,” you still need a PA license.

There is no modular distinction for PISP-like functionality vs actual acquiring, or at a scale level, to enable smaller players to innovate. No scale-based SPI/API separation; regulatory burden is uniform.

This makes it harder for new/small players to enter, compared to modular systems in EU/UK/SG.

As fintech evolves and use cases diversify, a one-size-fits-all licensing model stifles innovation. A tiered framework, such as PISP, SPI, MPI would allow regulators to categorize fintechs by scale and risk, enabling tailored oversight while fostering experimentation and growth

Out of the 73 fintechs I’ve profiled as a part of this piece, 54 of them have PA licenses. Apart from maybe 5 -10, the rest probably won’t ever use them. I rest my case.

Great read. Thanks for sharing this Ambika, I learn a lot whenever I read your articles.